our

news

AWARDS, ACCOLADES, PUBLICATIONS AND NEWS.

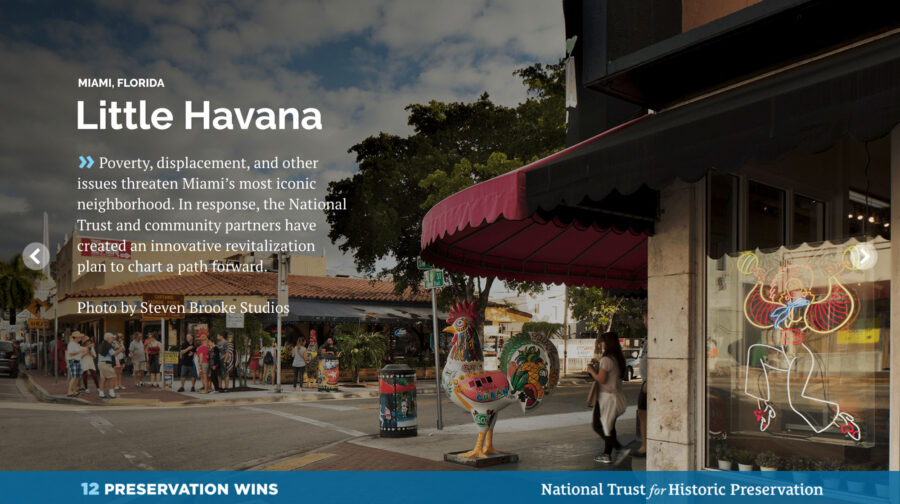

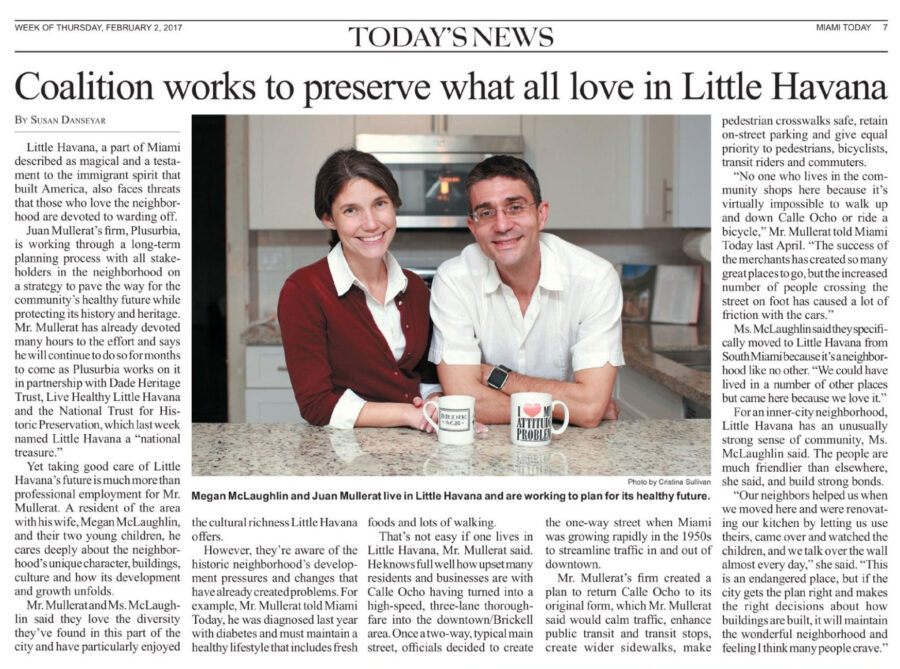

November 18, 2019 More:We're Saving Places By:Julia Rocchi Thanks to supporters and advocates like you, we at the National Trust are celebrating a year with wide-ranging victories, from hands-on work that enlivened old buildings, to legal successes that strengthened protection, to creative thinking that re-interpreted, re-imagined, and re-invigorated places telling America’s full history.To mark the occasion, we’re spotlighting 12 of our proudest preservation moments that epitomize our movement’s dedication and determination—and they’re all made possible by your support.8. Little HavanaMiami, FloridaAn international symbol of the role of immigrants in the American story, Little Havana—named a National Treasure in 2017—is Miami’s most iconic neighborhood. Yet poverty, displacement, and other issues threaten this vibrant community, prompting the National Trust to create a road map for improving life for Little Havana’s residents while protecting this one-of-a-kind place.In partnership with local organizations led by PlusUrbia Design, and developed with input from more than 2,700 residents, stakeholders, and public health advocates, the award-winning revitalization plan focuses on building a healthy, equitable, and resilient neighborhood that retains its unique character. Drawing on best practices from a variety of fields, the plan increases incentives, lowers barriers, and respects the existing heritage of Little Havana. With this innovative tool in hand, Little Havana now has a path forward that will help future generations continue to thrive.

BY ANDRES VIGLUCCISEPTEMBER 19, 2019 06:30 PM, UPDATED SEPTEMBER 19, 2019 06:43 PMSandwiched in between bustling Midtown Miami, the ultra-upscale Design District and the sizzling-hot Wynwood arts district, residents of the other Wynwood — its overlooked working-class residential enclave — figure it won’t be long before the redevelopment wave smacks them full bore.So they’re already gearing up for it.Rather than wait for the forces of gentrification to strike, residents and property owners in the Wynwood barrio section have organized in anticipation of its arrival. They formed a broad-based association, hired a prominent planner to draw up a map to guide revitalization, and will lobby public officials for zoning and other reforms to make sure they benefit and don’t get overrun.To distinguish themselves from the hipsters’ Wynwood to the south, and to reaffirm their neighborhood’s Hispanic immigrant and Puerto Rican roots, they’ve also given it a new name:Wynwood Norte.The new name made its formal debut Thursday evening, when the year-old Wynwood Community Enhancement Association unveiled a comprehensive vision plan for the neighborhood. It runs between Northwest 29th and 36th Streets from Interstate 95 to Miami Avenue, in the heart of Miami’s historic urban core.The roughly 35-block area includes three public schools and the Bakehouse Art Complex, which is planning a major expansion, as well as hundreds of single-family homes, duplexes and small apartment buildings. It was home for decades to Puerto Rican and later Cuban and Central American workers who labored in the garment district in the warehouses and factory buildings south of Twenty-ninth Street — what everyone today knows as Wynwood — before the industry went into sharp decline in the 1980s.Organizers of the unusual effort say they hope it will allow the low-income community of about 4,200 residents, one of Miami’s poorest, to retain not just its low scale and neighborly feel, but its people, too, even as it draws desperately needed new investment, homes and families to a neighborhood that’s been wanting for years.“I’ve seen all the changes, the ups and downs,” said association member Will Vasquez, an Army veteran who grew up in Wynwood. He owns several rental properties there and spends most weekends at his 90-year-old father’s home in the neighborhood. “Things have taken a big turn for the good. New people, investors are coming in. I am very excited.”But, Vasquez added, longtime stakeholders like himself don’t want dramatic changes, and that’s why they’ve banded together now.I would like to see the neighborhood kept more residential,” he said. “I don’t want to see Midtown or high rises. We have enough of that. I would like to see Wynwood Norte have its own identity. We want to make Wynwood Norte a place where people can come visit, eat at a restaurant. Very friendly, very walkable. And we hope to encourage people to fix their homes.”RESIDENTS LEAD CHARGEThe initiative in Wynwood Norte was prompted in part as residents watched other nearby neighborhoods attempt to fight wholesale changes only after rents and displacement shot up or major projects were already announced. By getting ahead of the game, they hope to set a template for developers and avoid divisive battles like that over the massive and controversial Magic City Innovation District plan in Little Haiti.Wynwood Norte residents and property owners huddle with planning consultants during a public workshop in May at Jose de Diego Middle School. COURTESY PLUSURBIA DESIGN They were also inspired by property owners in the Wynwood arts district who organized a business improvement district and got the city to approve special new zoning rules that encourage development of apartments and shops and foster improvements in the public realm, but restrict the scale and mass of new construction to ensure compatibility with the existing aesthetic.Wynwood Norte residents and property owners enlisted the support of the one large developer that’s announced plans for a significant project in the neighborhood. In 2017, Texas-based Westdale Real Estate Investment Management bought a block of mostly rundown residential properties and obtained city zoning approvals for a plan to raze them and build a low-scale housing and retail complex aimed at a range of incomes, including so-called workforce housing.A Westdale partner is a Wynwood Norte association director. The firm paid for the neighborhood vision plan by Plusurbia Design, the Miami planning firm that also developed the award-winning Wynwood arts district zoning plan, as well as a community-driven master redevelopment plan for Little Havana.Steve Wernick, an attorney who has represented Westdale and has been involved in the Wynwood Norte effort as a consultant and volunteer, said the developer’s interests mesh with those of the neighborhood: to ensure compatible development that will enhance the value of its project and its chances of success.But he stressed the impetus and direction are coming from the community, including leaders of nonprofits and service agencies in the neighborhood, such as Bakehouse interim director Cathy Leff, who is an association leader.Separately but in coordination with the association’s initiative, the Bakehouse has worked with Wernick on a strategic plan to renovate its historic building, an Art Deco former industrial bakery that houses some 60 artists’ studios, and add affordable housing for artists.“There is no other neighborhood that is planning the way this community is, “ Wernick said. “The community is saying, ‘Things are going to change, so let’s plan for that change. How can we grow in an appropriate way that allows the community to stay?’“It’s an invitation to the city and the county and the school board to take a look at neighborhood, to work with the association to implement the community vision. It’s definitely a balanced approach.”The Bakehouse Art Complex, housed in a former industrial bakery, in the Wynwood Norte neighborhood. BAKEHOUSE ART COMPLEX NOT ITS HEYDAYWynwood Norte has seen better days.Many Puerto Rican garment and factory workers owned homes in the neighborhood’s heyday, earning it the nickname of Little San Juan. But most Puerto Ricans are long gone, replaced by Cubans and later Central Americans, though the borincano flavor remains, mostly in names of places and institutions taken from the island.The city park, which includes a baseball diamond, is named Roberto Clemente Park, after the Puerto Rican major-league hall of famer. The local Catholic church, Mission San Juan Bautista, takes its name from Puerto Rico’s patron saint and its architecture from the island’s Spanish Colonial period. El Jibarito food market, named after the island name for its peasants, is still a draw on the neighborhood’s main street, Northwest Second Avenue. José de Diego Middle School honors a leader of Puerto Rico’s movement for independence from Spain. The San Juan Bautista Catholic mission church in Wynwood sits just north of the block that a Texas developer wants to redevelop. GALERIA DEL BARRIO But the Puerto Rican community that gave rise to the historic names is mostly a thing of the past. As the garment industry declined and disappeared, so did the garment workers who lived in the neighborhood. As it declined, Wynwood was plagued by crime, gangs and drug trafficking. In 1988, days of rioting ensued after undercover police bludgeoned a neighborhood drug dealer to death.Today, much of the population is a transient one, planners say. Over 80 percent of Wynwood Norte residents are renters, the association’s study says, though the population is trending younger. The neighborhood is dotted by vacant lots where houses were demolished; about 10 percent of Wynwood Norte is vacant land. Much of the remaining housing stock is deteriorated, though a few homes have been renovated in recent years by new owners moving into the area.Wynwood Norte residents today are among the city’s poorest. The median household income in the neighborhood is $19,800, and the median rent is $672, according to city of Miami planners. Fully a quarter of dwellings are officially designated affordable housing, including some public housing units, though some of it is not in good condition, the Plusurbia study says.Neighborhood businesses are faltering or disappearing. Dracula Video, for instance, long a mainstay on Northwest Second Avenue, moved out last year after the building that housed it was purchased, Vasquez said. Even the public schools are undersubscribed. Hartner Elementary and the Young Men’s Preparatory Academy are only at 50 percent capacity, planners say.Though there is plenty of low-cost housing, it’s in such bad shape that the neighborhood is attracting few families, Wernick said. That means it can’t capitalize on its status as one of Miami’s last largely residential zones in the urban core, he said.”It has remained very sleepy, but not in a way people are happy about,” he said. “There are lots of absentee landlords. Families that want to live in the neighborhood, they don’t have a lot of options. Professionals who want to live and work in the urban core don’t have a lot of options.” CAPPED HEIGHTThe Plusurbia plan would seek to foster compatible redevelopment through zoning tweaks to encourage incremental infill rather than large-scale projects, the typical Miami model. It calls for increasing allowable density while capping heights at four to five stories, and allowing developers extra square footage in exchange for payments into an affordable housing fund for the neighborhood.The plan also urges creation of a program of small grants to homeowners to underwrite repairs and renovations, and loosening of zoning rules to permit the addition of detached “in-law” quarters in single family home lots that allow for multi-generational living, or can be rented to boost family income and provide more affordable housing options.On the public side, the plan says the city and Miami-Dade must replace the neighborhood’s cracking sidewalks, improve street lighting and add to its thin tree canopy.The recommendations are the result of community consensus hammered out in public workshops, one-on-one meetings with local leaders, an online survey and walking tours of the neighborhood during which planners interviewed people on the street, said Plusurbia principal Juan Mullerat.“Everyone understood it needs to densify. Everyone was fearful additional density would displace them,” Mullerat said. “But overall we found there is room to grow within the neighborhood without displacing residents.“The whole idea here is that almost every recommendation is about mitigating displacement, increasing the affordable housing stock and supporting the existing residents.”One large problem that the plan would address, Mullerat said, is the suburban zoning assigned to Wynwood Norte by the city’s Miami 21 code, which does not allow sufficient density. The reason there is so much vacant land and little new housing in the area, he said, is that the rules make it unfeasible to develop there — a common problem in similar neighborhoods across the city, such as Little Havana.Those rules, Mullerat and other critics say, require too much parking onsite and too little building, making it almost impossible to physically fit it all in on a typical lot. That’s one reason why the typical Miami model of redevelopment is for an owner to amass multiple lots and build on a large scale, which displaces residents and helps drive up the cost of new housing.But that’s what’s likely in store for Wynwood Norte if the rules are not amended, Mullerat and Wernick argue.“If current conditions remain, doing nothing will lead to displacement, in my mind,” Wernick said.Yet Wynwood Norte already has the basics for success, stakeholders say. It is centrally located, dense, compact and eminently walkable, even if the sidewalks are cracking and the tree canopy thin. Social services, including a senior center, and Clemente Park are located on the business district main street. It’s a short stroll to Midtown Miami’s shops and restaurants and to Wynwood nightlife, both sources of jobs as well as diversion for residents.“It is because the location,” Vasquez said. “Wynwood is like a small little island, but there’s something always happening around it. Anybody that lives in Wynwood, you have everything at your fingertips. You don’t even need a car. You can take an Uber everywhere you need to go.”ARTISTS’ COLONYThe Bakehouse, meanwhile, has an ambitious plan that aims to turn it into a true community anchor.The center opened in 1986, after it was purchased by the city for an artists’ nonprofit to address a need for affordable working studios. At the time, artists were being pushed out of Coconut Grove by rising rents and redevelopment. Today, they’re being pushed out of the Wynwood arts district and downtown Miami.As Miami’s art scene grows, but affordable neighborhoods become increasingly rare, the need for housing for artists is a bigger need than ever, Leff said. The center is seeking zoning changes for its property to allow construction of up to 250 units of housing.Under a covenant signed when the city turned over the property, the bakery building must be preserved for artists’ use. So the development plan envisions a new residential building on the site, much of which is a parking lot or underused property, Leff said. The center expects to recruit investors or a developer to take on the housing portion, she said.The residential building would tie the Bakehouse more closely to the neighborhood, which would also benefit from the addition of hundreds of new residents to patronize businesses, Leff said.“We don’t want to overdevelop. Everybody recognizes the unique character of the neighborhood. We want to make sure whatever we do is in sync with the neighborhood,” Leff said.If the Wynwood Norte plan succeeds, Mullerat hopes it will become a new model for redevelopment in Miami — saving and enhancing what’s already there, instead of tearing it all down and building on a massive scale.“It’s been really a ground-up project. The neighbors have been very involved. It’s not developer-centric,” Mullerat said.“You are not going to do it tomorrow. We must create funding mechanisms that can fund all these lofty goals. It’s going to take time. But we need to start appreciating what we have.”

PlusUrbia's Megan McLaughlin contributed to the 2019 edition of Dade Heritage Trust Preservation Today Magazine.Her article is about the Vera Building, located in the OMNI Arts and Entertainment District of Miami. Read more about it below: Dade Heritage Trust was a key partner in the effort to create the Little Havana Me Importa Revitalization Plan. PlusUrbia is proud to collaborate with Dade Heritage Trust, helping to make Miami better, one step at a time.

Plusurbia Design was featured in the French magazine Urbanisme April, May, and June of 2019 issue. The article, written by Eric Firley, a Professor at the School of Architecture of The University of Miami, talkes about the City of Miami and its urban growth in spite of its battle with climate change. Plusurbia, along with other great firms in the City dedicated to urbanism, is mentioned for its groundbreaking work on the Wynwood Neighborhood Revitalization District, Little Havana Me Importa: Revitalization Master Plan, as well as the study of three Transit Oriented Development areas in Miami.

National Trust for Historic Preservation, PlusUrbia Design and local partners issue report with input from over 2,700 Little Havana residents and stakeholders.Miami (June 11, 2019) – With the goal of promoting the revitalization of the Little Havana neighborhood for current and future residents, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and PlusUrbia Design today released a master plan focused on building a healthy, equitable and resilient neighborhood community in Little Havana. The plan, put together over the course of more than two years and with the input of over 2,700 neighborhood residents and stakeholders and several local partners, brings together best practices and the latest thinking from a range of fields—from public health to urban planning to architectural design and historic preservation. It is the first plan of its kind to focus specifically on revitalizing and improving the quality of life for people in Miami’s most iconic neighborhood.The revitalization plan includes input from a collection of civic and non-profit organizations currently working in Little Havana, including: The Health Foundation of South Florida, Live Healthy Little Havana, Urban Health Partnerships and Dade Heritage Trust.From the time the National Trust named Little Havana a National Treasure in January of 2017, the Trust and its local partners led by Plusurbia Design, a local planning firm, have been focused on ways to retain the things that make this place one of America’s most beloved neighborhoods. While it is an iconic historic place, Little Havana is also a dynamic urban neighborhood whose residents face a range of challenges and threats, including poverty, sub-standard housing, displacement, poor transportation options and insufficient open space. This plan is an attempt to comprehensively address these challenges by bringing together an integrated set of national best practices from a diverse array of professional perspectives. Rather than a regulatory approach, the plan relies on increasing incentives, lowering barriers and respecting the existing heritage of Little Havana.“Little Havana is the heart and soul of Miami. It is also a longstanding symbol of the immigrant experience and one of the most essential places in America,” said Robert Nieweg, NTHP. “But there is no denying that this important place is also facing a range of threats, and its residents confront significant challenges on a daily basis, from sub-standard housing to poor transportation options to a lack of green space. In developing this plan, we listened to the concerns of thousands of local residents and stakeholders, and took advantage of the latest thinking in fields from public health to urban planning to architectural design and historic preservation to find solutions to these concerns. This is the first report of its kind, and webelieve it can be a road map for making life better for current and future Little Havanaresidents”"La Pequeña Habana is one of the best-known Latin-American barrios in the United States,"said Juan Mullerat, principal at PlusUrbia Design. "Though the neighborhood is one of Miami’spremier tourist destinations, those who spend time there know that its real value lies in itspeople and the legacies they have built over many generations in the neighborhood. This plan isinspired by the culture of Little Havana, and it seeks to ensure that this unique place and thepeople who created it will always have a home here." ABOUT THE NATIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATIONThe National Trust for Historic Preservation, a privately funded nonprofit organization, works to save America’s historic places. www.SavingPlaces.orgABOUT PLUSURBIA DESIGNPlusurbia Design is a Miami-based planning firm that designs contextual cities, towns and neighborhoodscollaboratively to create lasting value. www.plusurbia.comMEDIA CONTACTS: VIRGIL MCDILL, NATIONAL TRUST, 202.294.9187, VIRGILMCDILL@GMAIL.COMJUAN MULLERAT, PLUSURBIA DESIGN, 305.444.4850, JUAN@PLUSURBIA.COMRelated articles:WLRNhttps://www.wlrn.org/post/little-havana-revitalization-plan-released-will-now-go-actionThe Real Dealhttps://therealdeal.com/miami/2019/06/11/little-havana-could-be-redeveloped-like-wynwood/El Nuevo Heraldhttps://www.elnuevoherald.com/noticias/finanzas/acceso-miami/comunidades/article231432093.htmlWJCThttps://news.wjct.org/post/little-havana-revitalization-plan-released-will-now-go-actionCBS Miamihttps://miami.cbslocal.com/video/4102931-city-of-miami-unveils-plan-for-revitalization-of-little-havana/NBC Miamihttps://www.nbcmiami.com/on-air/as-seen-on/Mayor-Unveils-Plan-to-Revitalize-Little-Havana_Miami-511153152.htmlArchinecthttps://archinect.com/news/article/150141827/revitalization-plan-for-miami-s-little-havana-to-focus-on-more-affordable-housing-and-healthy-urban-livingCalle Ocho Newshttps://calleochonews.com/new-revitalization-plan-little-havana-me-importa/

BY ROB WILE AND JOEY FLECHASAPRIL 18, 2019 06:30 AMTri-Rail has yet to arrive at MiamiCentral Station, where Virgin/Brightline has long promised a downtown home for the stalwart commuter rail.But Tri-Rail continues to look ahead to stops that could serve rising populations along the way. A new study commissioned by the public rail company recommends potential local train stops in two Miami neighborhoods: Midtown and Little River.Coral Gables-based Plusurbia Design authored the report, which evaluates two spots in the Midtown corridor as suitable locations for a train platform in the near future, with some caveats. The planners wrote that any train stops must come with broader upgrades along surrounding streets, including redone sidewalks, better lighting and safer crosswalks, to encourage people to walk to the platforms.“You can put a station anywhere,” said Plusurbia principal Juan Mullerat. “But if you make it unpleasant to get there, then it will fail.” The study proposes a new train hub in Little River further in the future, with redeveloped residential and commercial buildings surrounding a station, all carefully planned with significant public input and sensitivity to residents who wish to stay in a gentrifying neighborhood.The report offers a vision of what transit-hungry citizens clamor for: connections that allow people to ditch cars and easily move between downtown and some of Miami’s most well-known neighborhoods.The business side of the idea is the tricky part. Plans for these train stops are contingent upon Tri-Rail’s access to tracks owned by Brightline, a private transit company. Planning from the two entities have moved at a pace Miamians have come to expect from big-picture mass transit projects: The date for Tri-Rail’s debut at MiamiCentral station, once expected in 2017, has been pushed back several times.A representative for Tri-Rail said there is now no projected date for when its first train will pull into downtown Miami. But in response to questions from the Miami Herald, a Brightline spokesman said it is working to install required safety controls for Tri-Rail to use its tracks, and is aiming to finish the work before the end of 2020.Still, politicians and local businesspeople endorse Tri-Rail’s idea. Last year, the Transportation Planning Organization — a countywide government agency that approves federally required plans and transportation policies — agreed to pay half the cost of smaller-scale pilot projects across Miami-Dade that would demonstrate people’s appetite for mass transit along corridors outlined by the countywide transportation blueprint known as the SMART Plan. Cities with the projects would pay the other 50 percent. Among those projects: A temporary train platform somewhere in the area of Midtown or the Design District.Miami Mayor Francis Suarez said that regardless of the operator, there’s an urgent need for traffic relief along the increasingly congested Biscayne corridor.“From a public policy perspective, from a quality of life perspective, it’s really important that this get resolved,” he said. “We cannot let this asset go underutilized.”Plusurbia’s report highlights two potential Midtown locations that could work for a train platform, if some significant changes were made — on the north end, bordering the Design District under the I-195 overpass, or further south, between Northeast 29th and 27th streets. Planners believe both would have a built-in ridership from the growing number of residential and commercial developments in Midtown, Wynwood, Edgewater and the Design District — along with the people from downtown and further north who wish to visit the area. The plan suggests there are fewer obstacles for a permanent platform south of 29th Street than under the I-195 overpass. The overpass site is north of Northeast 36th Street near a five-point intersection with Federal Highway and Northeast Second Avenue — the site of daily rush hour traffic snarls. The space on either side of the tracks between 27th and 29th streets would require the government to either acquire land or work with property owners to develop a station.One of those owners is interested. Bill Rammos, who’s invested in the Miller Machinery & Supply warehouse at 127 NE 27th St., told the Miami Herald he would be open to adapting the “old, underdeveloped warehouse” into a train station with commercial space.“I think that would help the whole neighborhood,” he said.Rammos considers the report a confirmation of what he sees every day: a growing community with new and obvious needs for those who live there, as well as people visiting the area — and cars are not the long-term solution.“More parking lots and garages for more cars ... we’ve been doing that for years,” he said. “And it’s not working.”For the temporary platform being pursued by the city of Miami, municipal planners still prefer the site north of 36th Street because the city’s parking authority already has land leased from the Florida Department of Transportation.“The report concludes that based on potential ridership, number of residents, and concentration of jobs, a location between Northeast 27th and 29th could better support a train station and would be better served by a train station than a location near 36th Street,” said city spokeswoman Stephanie Severino. “However, the specific station location near 29th would require land acquisition and there is not currently parking on-site.”.Plusurbia’s recommendations could guide the selection of a site for both a temporary and permanent platform, Severino said.Farther north and further into the future, the urban planning firm deemed a strip of land along Little River just north of Northeast 79th Street a viable home for a train stop accessible to residents of Little Haiti, Palm Grove, the Upper Eastside and Shorecrest. Planners see the potential for a transit hub, which could include a redevelopment of the Midpoint shopping center with new commercial and residential space, that balances gentrification already in motion with keeping current Little Haiti residents and the fabric of their neighborhood intact.The report emphasizes that maintaining the area’s cultural character and scale is crucial in a part of Miami already under pressure from developers, a point underscored by a current controversy about a large planned development about 17 blocks south of 79th Street. Plans for the massive Magic City Innovation District have fueled an intense debate among Little Haiti activists who agree the roughly 18-acre project would forever transform Little Haiti but not whether that change would be for better or for worse. Another 22-acre redevelopment proposal on Northeast 54th Street stalled last summer when activists objected.The need for reliable public transportation would likely have broad community support, though, as long as it does not come with real estate projects that would displace longstanding residents, the activists said. Meaningful community input would be key.“Any effort to relieve traffic that will not intrude on people’s way of life would be welcome,” said Marleine Bastien, a longtime area activist and director of the Family Action Network Movement.Last year, Northeast 76th Street resident Alisa Cepeda told the Herald she thought administrators ought to consider a train stop within walking distance of her neighborhood. With a station at 79th Street, she’d be able to make the seven-mile commute to work on just one train and a half-mile walk from MiamiCentral to her job on West Flagler Street. She’d have a much simpler commute than her current public transportation option of transferring from a trolley to a Metrobus to the Metromover to get to Government Center.A Metrorail passenger train rolls by the Brightline terminal in downtown Miami in March. Jose A. IglesiasJIGLESIAS@ELNUEVOHERALD.COM“I think it’s an absolutely wonderful idea,” she said Tuesday.It’s not a new idea, but the process to build a train platform is complicated by the ownership of the tracks, which forces public agencies to negotiate access to private infrastructure.Florida East Coast Industries (the parent company of Brightline, which is being renamed Virgin Trains USA) owns the tracks that Tri-Rail, operated by a public tri-county transit authority, wants to use. Tri-Rail was supposed to have arrived at MiamiCentral by 2017, according to one of the earliest presentations Tri-Rail published showing both Brightline (then All Aboard Florida) and Coastal Link projects.Today, Tri-Rail executive director Steven Abrams says Tri-Rail and Brightline have a “cooperative, complementary relationship.”“We really serve different residents in South Florida,” he said. “Our service is very much for the daily commuter. We stop every two miles along our route in various cities, we have a lower price point on our ticket. Whereas Brightline, it’s three stops, it’s more geared toward the tourist or businessperson in the area.”While there is some overlap, one that would increase as Tri-Rail serves as a conduit for Brightline passengers, “coexisting is fine.”“They made it possible for us to go into MiamiCentral Station by reserving a platform and working cooperatively with us,” he said. “They think the same of us. If you asked, they have a cooperative relationship with Tri-Rail.”Yet the opportunity is huge.“We would grow tremendously if we were able to extend our existing service through downtowns of major coastal cities,” he said.Aileen Boucle, executive director of Miami-Dade’s Transportation Planning Organization, said the goal has remained for Tri-Rail riders to have another stop before downtown on the day the train first pulls into MiamiCentral, even if it’s a temporary location while a permanent station is planned.“Having that service would allow residents and commuters to benefit from that project immediately,” she said.For Suarez, one of several Miami-Dade municipal politicians who sit on the planning organization’s board, at least a stop in the Midtown/Wynwood/Design District is necessary today — so much so that he thinks a temporary platform should be built wherever most feasible in the short term to demonstrate the potential ridership.“I’d rather have something to start proving the concept now than wait for something permanent,” he said.A Tri-Rail train heads north from the Northwest 79th Street station in Miami-Dade. C.M. GUERREROEL NUEVO HERALDRead more here: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/article229002739.html#storylink=cpy

Miami's Shenandoah: a neighborhood ahead of its timePlusUrbia is excited to be working to survey the Shenandoah neighborhood along with Dade Heritage Trust.POSTED ON MARCH 21, 2019 AT 1:18 PM.WRITTEN BY THE NEW TROPIC CREATIVE STUDIOA look at the 1800 block of SW 11th Terrace between 1920-1930 in the Shenandoah neighborhood of Miami. (Photo by Gleason Romer)WHAT IT IS: Shenandoah, a neighborhood just southwest of downtown Miami, is one largest collections of 1920s and 1930s architecture that the city or state hasn’t studied or documented.Megan McLaughlin moved to the neighborhood 10 years ago because she exhausted of her 90 minute commute to downtown. With two toddlers, she felt like she was missing out on so much time with them. So she and her husband moved to Shenandoah, where they can walk everywhere and catch a bus to downtown.McLaughlin and Chris Rupp from the Dade Heritage Trust have partnered to survey the neighborhood and put together a report with the data they collect. With a grant from the state, they’ll create a file for each of the 650 properties in Shenandoah that will include the history of the house, previous owners and residents, and the prominent architectural features.MOST SURPRISING FACT: According to McLaughlin, Shenandoah is one of the most diverse neighborhoods in Miami, a city that’s already very inclusive of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds. McLaughlin said that city directories show that the neighborhood was at some point home to Jewish, Middle Eastern, and Russian families. Cuban and other refugee families also settled there in the 1960s.WHY IT IS IMPORTANT: Shenandoah was one of the first suburban developments outside of downtown and has always been ahead of its time, McLaughlin said.“It was different from Coral Gables and Miami Shores and some of these other maybe more known suburbs because it was diverse from the beginning,” she said. “You had already a mix of duplexes, houses, little apartment buildings, corner stores, all of these things that I think the new urbanism and other planning folk talk about that now as the gold standard of a ‘good urban neighborhood’ but Shenandoah had it 100 years ago.”HOW TO GET INVOLVED: If you’re interested in volunteering to help conduct the survey or organize the collected data – or organize a similar survey for your own neighborhood – McLaughlin said you can contact the Dade Heritage Trust.Find out more information by reading the article written by THE NEW TROPIC CREATIVE STUDIO through the link below:https://thenewtropic.com/neighborhood-spotlight-working-to-document-shenandoahs-historic-architecture/

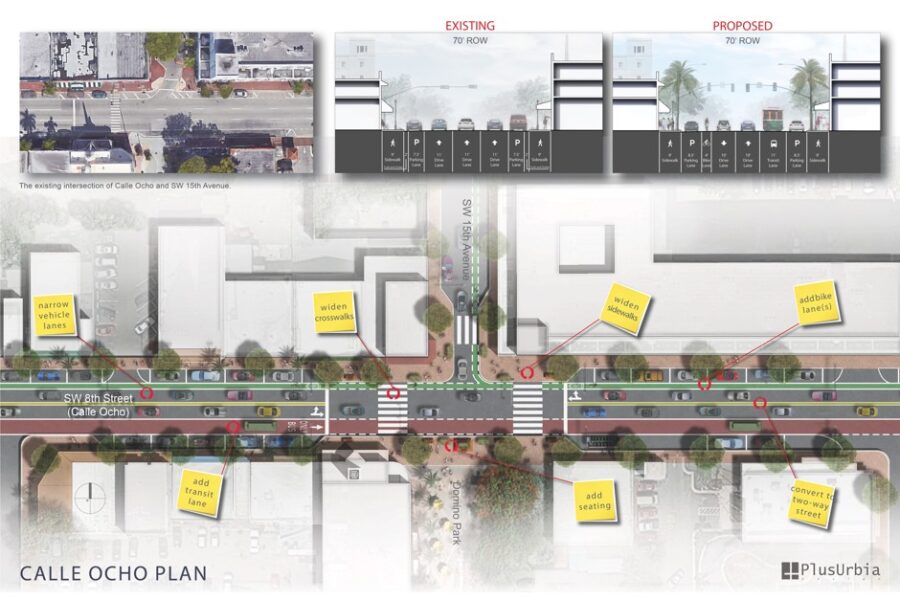

MIAMI - PlusUrbia Design’s unique vision to create a parklet out of parking spaces in urban Miami will be unveiled this month. The Miami-based studio’s solution for a low-cost, high-impact urban oasis will open to the public at 10 a.m. Friday September 21 on NE 3rd Avenue and NE 1st Street in Downtown Miami.While legislation to regulate parklets is still being ironed out, the innovative studio brainstormed ways of making a demonstration parklet that didn’t need a permanent location. The studio has designed and built a 70 SF parklet on wheels – a tiny park that fits into no more than two parking spaces.The idea for the Tropical Trailer Park was the winner of the 2016 Miami Foundation Public Space Challenge.The Tropical Trailer Park will move to different locations, many lacking open space, to inspire people to find ways of making their neighborhood more livable. This Do It Yourself method of providing open space where none exists provides a quick solution to areas starved for civic amenities. “Miami’s lack of open space has an adverse effect on our health and livability. Our studio decided to build a parklet that provides a mobile solution to enhance our streets – a park on wheels - as a gift to our city.”-Juan Mullerat, Principal of PlusUrbia Design PlusUrbia is known for its urban interventions and advocacy in Miami including the Master Plan of Little Havana, Coconut Grove, the redesign of Calle Ocho and Complete Districts. Looking for more information on the Trailer Park? Follow the link! trailerparklet.com Related articles: The Big Bubble Miami

Glad our capacity crowd workshop and innovative online survey drove a plan that the Grove BID can use to steer economic development, preservation, walkability and unique village character for the next decade.

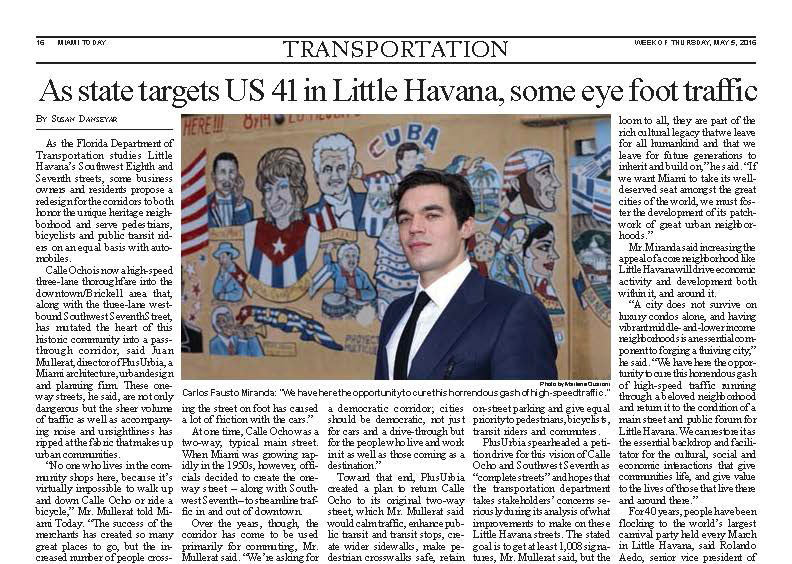

PlusUrbia Design was honored by the Miami Today's 2018 Gold Medal Awards competition earning the Bronze Medal for an organization.Our boutique studio was eligible for the award because it won the 2017 American Planning Association’s APA National Economic Development Plan Award for its Wynwood Neighborhood Revitalization District plan. PlusUrbia earned the Gold Medal Award for its context-sensitive, community-based planning. It submitted a brief portfolio to the Miami Today judges that emphasized innovative urban design that promotes multimodal mobility, affordability, and connectivity that enhances quality of life. Our studio has emphasized healthy living through access to open space, public transit, affordable housing, mixed-use development, active recreation and safe complete streets.“My father, a lawyer and published author, wrote about ethics and the social role and responsibilities of Corporations, instilled in me a sincere sense of Community Service,” said PlusUrbia Founding Principal Juan Mullerat. “This instilled in me this sense of service, which we practice in our studio through non-profit projects.”PlusUrbia has donated more than 1,000 professional hours to the ongoing Master Planning for a Healthy and Resilient Little Havana, in collaboration with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Health Foundation of South Florida. Our 12-person studio has devoted more than two years listening to residents and crafting an Action Plan to improve the lives of one of the poorest, most unique, socially and demographically rich neighborhoods in the nation.“Our office has worked very hard and continues to push the envelope, delivering innovative solutions on issues that shape our built environment,” Mullerat said. “Our projects focus on transportation, affordable housing strategies, open space – all of which have profound impact on everybody’s life.”Whether it is a Transit Oriented Development, Community Redevelopment Agency, Business Improvement District, Transit Corridor, Action Plan or Visioning Exercise – PlusUrbia’s work focuses on outcomes that support healthy living in urban areas.Miami Today, celebrating its 35th year, is a weekly newspaper that reaches more than 68,000 readers and covers government, development, design, real estate, business, finance, health care and related issues that impact the future of Miami. Link to digital article: http://www.miamitodaynews.com/2018/06/05/gold-medal-awards-to-six-tibor-hollo-named-lifetime-achiever/

KEYS TO A LIVABLE COMMUNITY FOR ALLBy Steve WrightPhoto by Andy RyanYou’ve just moved into your new home. In addition to guiding you through the offer/ counter offer, financing, inspection and closing — your enlightened REALTOR® has found a dwelling that meets your needs as a person with a physical disability.There's at least one level entrance, wider doorways, a modified bathroom with a roll-in shower, raised commode with safety grab bars and a sink you can roll up to from a wheelchair. Though it has taken a ton of research, only half the battle is won. The inside of the home you purchased might be a show case of barrier-free access, but what about your neighborhood? Is there a nearby commuter train or major bus route? Are they accessible? Can you get to them safely via wide sidewalks and pedestrian-friendly crosswalks? Is the neighborhood park readily accessible, or filled with barriers?For a person with a disability — and according to the U.S. Census, there are 57 million disabled Americans — nothing is more relevant to quality of life than the old real estate adage “location, location, location.” But savvy REALTORS® know that location does not mean merely good schools, low crime and rising real estate values. When serving a client with a mobility impairment — and 16 million Americans use wheelchairs, canes, crutches, or walkers for mobility — a real estate professional should be familiar with the concepts of Universal Design and Inclusive Mobility. A real estate professional should be familiar with the concepts of Universal Design and Inclusive Mobility.Universal Design is the design of products and environments to be usable by all people. Universal Design is defined as: “The design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” The concept was developed by the late architect Ronald L. Mace, founder of the Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University. The beauty is that Universal Design is not some segregated approach only relevant to wheelchair users. Its principles make spaces welcoming and easy to use for elderly people, young children, parents pushing strollers and others.Inclusive Mobility is an approach to designing the public realm in a way that is accessible to all people — from the moment they leave their door until they arrive at their destination: work, school, the supermarket, the park, shops, etc. The approach combines increased pedestrian access and safety with barrier-free public transit. Complete Streets is the concept that the roadway should not be designed primarily for cars — with mobility for pedestrians, bicyclists, transit riders and others merely an afterthought. Complete Streets — a rapidly-growing concept in the planning and transportation fields — advocates for calmed traffic, wide sidewalks, dedicated bike lanes, safe crosswalks, curb ramps for disabled folks and well-defined transit stops, ideally with shelters to protect all riders from the elements.Inclusive Mobility extends to public transit, which is especially important to commuters in larger cities where traffic congestion is doubling and tripling commute times. Although the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has been federal civil rights law since 1990, transit is far from perfect for people with disabilities. In New York, a city that thrives on subway trains moving millions of people to work, just 117 of its 472 subway stations are fully accessible. Only 67 percent of Chicago’s train stations are fully accessible to people with disabilities. The key is to work with elected officials to retrofit stations. Some communities have gotten meaningful results. Washington D.C.’s 91 Metro train stations are 100 percent accessible.Even in medium-sized cities, public transit often is the only affordable way for a wheelchair user to get from home to work, college or other crucial destinations. Accessible consumer van upgrades — installing lifts, ramps, safety tie-downs, and automated systems that allow for transfer from a wheelchair to the driver’s seat — can cost upward of $75,000, and thousands more per year to fuel, maintain, insure and park. That makes it cost-prohibitive for low- to moderate-income families and barely attainable to even middle- to upper-income households.Courtesy of Metropolitan Transportation AuthorityCourtesy of Metropolitan Transportation AuthorityMany government officials embrace ride-share and transportation network companies, like Uber and Lyft, as the solution to the expense of vehicle ownership, traffic congestion and the high cost of adding transit lines. But these app-based services are provided by independent contractors who typically drive sedans and SUVs, meaning virtually no ride share vehicles can accommodate those who use power wheelchairs or other large motorized devices.Activist John Wetmore produces Perils for Pedestrians, a public affairs series on public access cable television stations in 150 cities in the United States. While the videos are aimed at pedestrian safety for all, Wetmore is acutely aware that something as simple as a public sidewalk full of obstructions can eliminate freedom of mobility for a person with a disability.“Often those responsible for blocking the sidewalk will say that it is alright because they meet the minimum legally required by the ADA. That is like bragging that you passed because you got a D on your report card,” Wetmore said. “We should expect better than that. Rather than striving for a D, they should attempt to get an A by putting the obstructions entirely out of the sidewalk.”Wetmore’s companion website has galleries that illustrate bad design examples, such as a parking meter in the middle of a sidewalk, a curb ramp constantly prone to flooding storm water, a street so full of sidewalk café tables that a wheelchair user has no room to maneuver, concrete so damaged and poorly maintained that it blocks wheelers and creates a tripping hazard for all. Another photo shows a streetlight control panel placed in the center of a heavily-traveled sidewalk right where a wheelchair user would crash into it after negotiating a curb ramp.Along with many blunders, Wetmore highlights an excellent example of a wheelchair-accessible sidewalk in Augusta, Georgia, that meets pedestrian access standards in the PROWAG (Public Right of Way Accessibility Guidelines) under the ADA.Everything about transportation — both urban and rural — will likely be transformed over the next decade. Transportation service providers such as Uber and Lyft, and autonomous self-driving vehicles are already changing the landscape. Some fear that suburban transit service will disappear altogether.WMATA photograph by Larry LevineSo what exactly does the future hold, and how do we serve everyone? These are some of the questions that land use and transportation planner Jana Lynott AICP, MA, seeks to answer.Lynott manages the American Association of Retired Persons’ (AARP) transportation research agenda. She is responsible for the development of AARP’s policy related to transportation and other livable communities issues.“It’s one thing to understand the law and the regulations, but another to understand the design experience. All of us as planners need to wrap our heads around the principles of universal design and think through what that means,” said Lynott.Lynott believes that these principles are essential to the design of better, more disability-friendly transit systems. For example, even compliantly designed buses may miss the mark if they service a bus way where poorly designed stops result in bus ramps that must be extended at a steep slope.Said Lynott: “The devil is in the details with design.”Lynott believes that if design is to truly be inclusive, it must balance the sexy with the sensible. This applies to developments on the cutting edge, such as self-driving vehicles, like autonomous buses and shuttle buses.Some of the vehicles currently in beta incorporate hip design details such as papasan, or bowl chairs. But the chic design doesn’t serve all riders. Public transit often is the only affordable way for a wheelchair user to get from home to work. WMATA photograph by Larry LevineAccessible civic space is crucial to providing a highly livable community. “An older adult — even one who walks — may have difficulty getting back upright from the seats. Standard transit bus designers have already figured out how to design accessible seating. We shouldn’t forget what we’ve already done that works,” said Lynott.The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) has developed “The Transit Street Design Guide” for the development of transit facilities on city streets, and for the design and engineering of city streets to prioritize transit while improving transit service quality for all.The NACTO guide incorporates universal design features, which are critical throughout the transportation network, making it possible for any street user to comfortably and conveniently reach every transit stop. Universal street design facilitates station access, system equity, and ease of movement for all users, especially people using wheelchairs or mobility devices, the elderly, people with children and strollers, and people carrying groceries or packages.While clear pedestrian paths, safe crosswalks and public transit that is accessible — via gently-sloped ramps to boarding stations, elevators, or lift-equipped buses — is a key part of the equation, accessible civic space is equally crucial to providing a highly livable community for people with disabilities and their families.Michael Van Valken burgh Associates placed so much emphasis on Universal Design in its creation of Brooklyn Bridge Park that the park’s website has a prominent link that details all of the accessible features on its piers and greenway that stretches for more than a mile along the East River waterfront.Crown Fountain in Chicago's Millennium Park was recognized by the Paralyzed Veterans of America for its Universal Design. Photo courtesy of PVA.Handrails and gentle slopes provide Universal Design on Squibb Park Bridge designed by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates. Photo by Andy Ryan.“Ramped pathways and bridges are less prone to technical difficulties, and they also create a stronger continuity of landscape experience that is part of the enjoyment of being in a park,” said the Van Valkenburgh team. “Once you decide that it is important to connect two spaces through the landscape, it seems worth the effort to make sure that everyone can use it.”The Van Valkenburgh firm embraces creative approaches to designing for all, opting for landscape-based solutions to accessibility that use gentle slopes instead of lifts or elevators that require more maintenance and are much more likely to break down.Photo by Andy RyanCrown Fountain in Chicago's Millennium Park is noted for being accessible to visitors of all ages and mobility. Photos courtesy of Millennium Park Foundation.Accessibility requirements provide opportunities to build pathways that are more engaging. “In some cases, accessibility requirements provide opportunities to build pathways that are more engaging — for instance a curved pathway that directs your views to the landscape context rather than a straight procession with an unchanging perspective,” the Van Valkenburgh team said. “We are strong advocates for building accessibility into the fundamental structure of a project, rather than looking at it as an obligation or an afterthought. Ultimately, the goal is to make accessibility feel effortless so that everyone can enjoy the landscape on the same terms.”Toronto, Canada-based nonprofit 8 80 Cities has challenged more than 250 cities on five continents to design their streets and public spaces to be easily accessible for both an eight-year-old and an 80-year-old.“We focus on children and older adults because we know that modern childhood and older adulthood in cities around the world is increasingly characterized by limited freedom and independence, reduced opportunities for social engagement and physical activity in public spaces, and few opportunities to participate in community building and decision-making,” said Amanda O’Rourke, executive director of 8 80 Cities.She said children, older adults and people with disabilities often have the most to benefit from living in connected, walk able and bike able communities with access to great parks and public spaces.Crown Fountain in Chicago's Millennium Park is noted for being accessible to visitors of all ages and mobility. Photos courtesy of Millennium Park Foundation.“One of the famous quotes from our Founder and Chair of the Board Gil Penalosa is ‘we have to stop building our cities as if everyone was 30 years old and athletic,’” O’Rourke said. “Streets often account for at least 25 percent of a city’s public space (in some cities close to 40 or 50 percent) and that means they are spaces that belong to all of us. The way we have designed cities for the last 60 years has been much more focused on the mobility of cars, than on the health and happiness of people. And this car-centric planning has been disproportionately bad for vulnerable road users — children, older adults, people with a disability and low-income communities.”Chicago’s 25-acre Millennium Park earned a Barrier-Free America Award from the Paralyzed Veterans of America — presented to architect Edward K. Uhlir, executive director of the Millennium Park Foundation.The park’s original grandiose design featured lots of grand staircases and other elements that were not conducive to Universal Design. The late Uhlir is credited with working with additional designers to greatly increase accessibility via ramps, gentle slopes and barrier-free play areas.“My office saw (the original plan with grand staircases and other barriers to mobility) and said ‘no way are you going to build a big park in downtown Chicago with stairs that are not accessible to people with disabilities,’” said Denise Arnold, a private practice architect and inclusive design specialist who worked for Chicago’s Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities while Millennium Park was being developed. We have to stop building our cities as if everyone was 30 years old and athletic. The Crown Fountain, designed by Catalan artist Jaume Plensa and executed by Krueck and Sexton Architects of Chicago, is composed of a black granite reflecting pool placed between a pair of 50-foot glass brick towers that display digital videos on their inward faces.“The fountain is the coolest thing in the world and (the reflecting pool) has no more than quarter inch lip at any place,” Arnold said of the grand piece of usable public art. “The fountain has giant glass block towers where water spouts 12 feet high off the ground and comes down on kids. It is a completely accessible mini water park. You see people of all abilities running around that fountain and playing in it.”James Corner Field Operations, the New York-based landscape architecture and urban planning studio that is best known as the project lead for the High Line in Manhattan, has heavily incorporated universal design into the Underline in Miami. The Underline’s vision is to transform 10 miles of land below Miami’s Metrorail into an iconic linear park, world-class accessible urban trail, to be completed by 2022.The future South Miami Hospital "Healing Garden" will feature native therapeutic plants and will open onto The Underline, promoting interaction between users of both spaces.Photos © James Corner Field Operations, Courtesy of Friends of the Underline.“The key criteria for the design of these two primary components are to provide a safe environment for users navigating the trail at different speeds and physical abilities,” says Isabel Castilla, lead designer for the Underline and a senior associate at James Corner Field Operations.The Underline will replace an underutilized, not universally accessible paved trail known as the M-Path. The existing M-Path is hampered by dozens of street crossings that are very dangerous for wheelchair users, children, and slow-walking pedestrians. Field Operations’ plan will increase safety and improve visibility at intersection crossings, meeting the needs of people with visual, hearing, cognitive, and other impairments, as well as mobility difficulties, Castilla said. Steve Wright is an award-winning journalist and the communications leader for PlusUrbia Design, a Miami-based urban design firm that incorporates Universal Design and Inclusive Mobility into its work. The studio’s Wynwood Neighborhood Revitalization was honored with the 2017 APA National Economic Development Plan Award.www.plusurbia.com The future approach to Brickell Station will be a gathering space for residents, showcasing the existing oolite outcrop.Photos © James Corner Field Operations, Courtesy of Friends of the Underline.Link: http://www.oncommonground-digital.org/oncommonground/summer_2018_fair_housing_and_more/MobilePagedReplica.action?pm=2&folio=46#pg46

BY ANDRES VIGLUCCIaviglucci@miamiherald.comMarch 08, 2018 05:30 PMUpdated 11 hours 21 minutes ago Some time in the very near future, Wynwood will get something quite avant-forward, at least for Miami: A street in which cars, bikes and pedestrians share the pavement on an equal footing.It’s called a “woonerf,” it’s inspired by the Dutch, and it’s coming to four blocks in the heart of Wynwood. On Thursday, Miami commissioners approved a contract with a Brooklyn, N.Y., firm that will design the city’s first true shared street.In a woonerf (pronounced voo-nerf), planters, landscaping and bollards serve to slow down motorists enough so that people on foot and in cars or on bikes can mix freely and safely.For the formerly industrial Wynwood district, now a flowering arts and entertainment mecca, the woonerf affords an opportunity for badly needed green and welcoming public space. It would also provide a secondary focus for its lively street life west of the neighborhood’s main drag, Northwest Second Avenue.The idea is to transform the scruffy Northwest Third Avenue right-of-way between Northwest 29th Street, the district’s northern border, and 25th Street, where the street dead-ends, providing a natural terminus for the woonerf. The street is today distinguished largely by the Wynwood Building, the warehouse prominently painted in a zebra-stripe design. The zebra-striped Wynwood Building sits on Northwest Third Avenue, which will be transformed into a “woonerf,” a street in which cars, bikes and pedestrians share the pavement on an equal footing. Ger Ger Getty Images But can the woonerf concept stand up to the belligerent carelessness of so many Miami motorists? Experts say the devil is in the design details, but woonerfs have proven themselves all over the world, and are increasingly popping up in U.S. cities.It does require care and alertness by all users, but that’s why the woonerf works, they say. Beyond some basic principles, their design can be tailored to local circumstances.“There’s no real guidelines for what a woonerf needs to be, so you can be creative,” said Juan Mullerat, principal at Coconut Grove-based urban design firm PlusUrbia, which first came up with the idea for a Wynwood woonerf when it drew up a new zoning plan for the burgeoning hipster district. “The idea is slow cars down and provide an equal use of the street.”For the Wynwood blueprint, the city is turning to Local Office Landscape and Urban Design, whose co-principal, architect Walter Meyer, grew up in Miami. The firm won a competition for the $392,900 design contract.Separately, the commission also approved a $615,140 contract with Miami-based Arquitectonica GEO for a broader tree and landscape master plan for Wynwood, a former warehouse district sorely lacking in greenery.Local Office, which designed the temporary Grand Central Park in downtown Miami, also collaborated on the design for the recently completed makeover of Miracle Mile and a block of adjacent Giralda Avenue in Coral Gables.Giralda, the suburban city’s famed restaurant row, was redesigned in a woonerf-like fashion, with no curbs or sidewalks and trees planted in the center of the street. But the city has closed it off to cars in a two-year experiment, turning it into a pedestrian plaza filled with outdoor cafe and restaurant tables.The recently remade restaurant row in Coral Gables, Giralda Plaza, was designed as a shared street but is functioning as a car-free pedestrian plaza in a two-year experiment.Courtesy City of Coral Gables This modern version of the shared street originated in the Netherlands in the 1970s, thus the Dutch name. It has spread around the world, though the concept of people on foot mixing it up with horses, carriages, bicyclists, trolleys and, yes, even motorcars is an old one.Before urban streets were segregated for use primarily by cars, with pedestrians relegated to sidewalks, different modes of transportation mixed in freewheeling fashion in cities across the world and in the United States.Modern woonerfs are intended to put the pedestrian first. They often have no signage and no curbs, to avoid tripping obstacles and to provide a feeling of expansive shared space. Often they contain cues such as colored pavement or bollards to demarcate primary areas for pedestrians and cars.A rendering of a concept for a woonerf in a new pedestrian friendly zoning district in eastern Hialeah.PlusUrbia Because of Miami-Dade County road-safety rules, though, the Wynwood woonerf may have to provide separate primary zones for motor vehicles and pedestrians, perhaps through markings or signage, said Jorge Kuperman, an architect whose office sits on Giralda Plaza and who served on the steering committee for the makeover.“We are the country of regulations, but it can be as minimal as landscaping,” Kuperman said. “It’s a great model, obviously. You can go to Lisbon or Madrid. All you see are urban interventions that are absolutely curbless. They are not from last year. They’re from long ago. And they’re designed mainly for the life of pedestrians.” Link to article: http://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/article204194634.html