our

news

AWARDS, ACCOLADES, PUBLICATIONS AND NEWS.

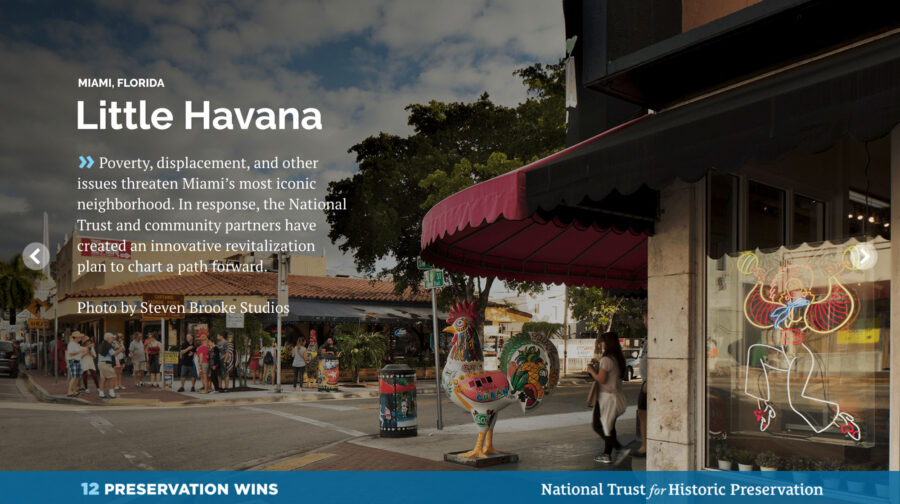

November 18, 2019 More:We're Saving Places By:Julia Rocchi Thanks to supporters and advocates like you, we at the National Trust are celebrating a year with wide-ranging victories, from hands-on work that enlivened old buildings, to legal successes that strengthened protection, to creative thinking that re-interpreted, re-imagined, and re-invigorated places telling America’s full history.To mark the occasion, we’re spotlighting 12 of our proudest preservation moments that epitomize our movement’s dedication and determination—and they’re all made possible by your support.8. Little HavanaMiami, FloridaAn international symbol of the role of immigrants in the American story, Little Havana—named a National Treasure in 2017—is Miami’s most iconic neighborhood. Yet poverty, displacement, and other issues threaten this vibrant community, prompting the National Trust to create a road map for improving life for Little Havana’s residents while protecting this one-of-a-kind place.In partnership with local organizations led by PlusUrbia Design, and developed with input from more than 2,700 residents, stakeholders, and public health advocates, the award-winning revitalization plan focuses on building a healthy, equitable, and resilient neighborhood that retains its unique character. Drawing on best practices from a variety of fields, the plan increases incentives, lowers barriers, and respects the existing heritage of Little Havana. With this innovative tool in hand, Little Havana now has a path forward that will help future generations continue to thrive.

BY ANDRES VIGLUCCISEPTEMBER 19, 2019 06:30 PM, UPDATED SEPTEMBER 19, 2019 06:43 PMSandwiched in between bustling Midtown Miami, the ultra-upscale Design District and the sizzling-hot Wynwood arts district, residents of the other Wynwood — its overlooked working-class residential enclave — figure it won’t be long before the redevelopment wave smacks them full bore.So they’re already gearing up for it.Rather than wait for the forces of gentrification to strike, residents and property owners in the Wynwood barrio section have organized in anticipation of its arrival. They formed a broad-based association, hired a prominent planner to draw up a map to guide revitalization, and will lobby public officials for zoning and other reforms to make sure they benefit and don’t get overrun.To distinguish themselves from the hipsters’ Wynwood to the south, and to reaffirm their neighborhood’s Hispanic immigrant and Puerto Rican roots, they’ve also given it a new name:Wynwood Norte.The new name made its formal debut Thursday evening, when the year-old Wynwood Community Enhancement Association unveiled a comprehensive vision plan for the neighborhood. It runs between Northwest 29th and 36th Streets from Interstate 95 to Miami Avenue, in the heart of Miami’s historic urban core.The roughly 35-block area includes three public schools and the Bakehouse Art Complex, which is planning a major expansion, as well as hundreds of single-family homes, duplexes and small apartment buildings. It was home for decades to Puerto Rican and later Cuban and Central American workers who labored in the garment district in the warehouses and factory buildings south of Twenty-ninth Street — what everyone today knows as Wynwood — before the industry went into sharp decline in the 1980s.Organizers of the unusual effort say they hope it will allow the low-income community of about 4,200 residents, one of Miami’s poorest, to retain not just its low scale and neighborly feel, but its people, too, even as it draws desperately needed new investment, homes and families to a neighborhood that’s been wanting for years.“I’ve seen all the changes, the ups and downs,” said association member Will Vasquez, an Army veteran who grew up in Wynwood. He owns several rental properties there and spends most weekends at his 90-year-old father’s home in the neighborhood. “Things have taken a big turn for the good. New people, investors are coming in. I am very excited.”But, Vasquez added, longtime stakeholders like himself don’t want dramatic changes, and that’s why they’ve banded together now.I would like to see the neighborhood kept more residential,” he said. “I don’t want to see Midtown or high rises. We have enough of that. I would like to see Wynwood Norte have its own identity. We want to make Wynwood Norte a place where people can come visit, eat at a restaurant. Very friendly, very walkable. And we hope to encourage people to fix their homes.”RESIDENTS LEAD CHARGEThe initiative in Wynwood Norte was prompted in part as residents watched other nearby neighborhoods attempt to fight wholesale changes only after rents and displacement shot up or major projects were already announced. By getting ahead of the game, they hope to set a template for developers and avoid divisive battles like that over the massive and controversial Magic City Innovation District plan in Little Haiti.Wynwood Norte residents and property owners huddle with planning consultants during a public workshop in May at Jose de Diego Middle School. COURTESY PLUSURBIA DESIGN They were also inspired by property owners in the Wynwood arts district who organized a business improvement district and got the city to approve special new zoning rules that encourage development of apartments and shops and foster improvements in the public realm, but restrict the scale and mass of new construction to ensure compatibility with the existing aesthetic.Wynwood Norte residents and property owners enlisted the support of the one large developer that’s announced plans for a significant project in the neighborhood. In 2017, Texas-based Westdale Real Estate Investment Management bought a block of mostly rundown residential properties and obtained city zoning approvals for a plan to raze them and build a low-scale housing and retail complex aimed at a range of incomes, including so-called workforce housing.A Westdale partner is a Wynwood Norte association director. The firm paid for the neighborhood vision plan by Plusurbia Design, the Miami planning firm that also developed the award-winning Wynwood arts district zoning plan, as well as a community-driven master redevelopment plan for Little Havana.Steve Wernick, an attorney who has represented Westdale and has been involved in the Wynwood Norte effort as a consultant and volunteer, said the developer’s interests mesh with those of the neighborhood: to ensure compatible development that will enhance the value of its project and its chances of success.But he stressed the impetus and direction are coming from the community, including leaders of nonprofits and service agencies in the neighborhood, such as Bakehouse interim director Cathy Leff, who is an association leader.Separately but in coordination with the association’s initiative, the Bakehouse has worked with Wernick on a strategic plan to renovate its historic building, an Art Deco former industrial bakery that houses some 60 artists’ studios, and add affordable housing for artists.“There is no other neighborhood that is planning the way this community is, “ Wernick said. “The community is saying, ‘Things are going to change, so let’s plan for that change. How can we grow in an appropriate way that allows the community to stay?’“It’s an invitation to the city and the county and the school board to take a look at neighborhood, to work with the association to implement the community vision. It’s definitely a balanced approach.”The Bakehouse Art Complex, housed in a former industrial bakery, in the Wynwood Norte neighborhood. BAKEHOUSE ART COMPLEX NOT ITS HEYDAYWynwood Norte has seen better days.Many Puerto Rican garment and factory workers owned homes in the neighborhood’s heyday, earning it the nickname of Little San Juan. But most Puerto Ricans are long gone, replaced by Cubans and later Central Americans, though the borincano flavor remains, mostly in names of places and institutions taken from the island.The city park, which includes a baseball diamond, is named Roberto Clemente Park, after the Puerto Rican major-league hall of famer. The local Catholic church, Mission San Juan Bautista, takes its name from Puerto Rico’s patron saint and its architecture from the island’s Spanish Colonial period. El Jibarito food market, named after the island name for its peasants, is still a draw on the neighborhood’s main street, Northwest Second Avenue. José de Diego Middle School honors a leader of Puerto Rico’s movement for independence from Spain. The San Juan Bautista Catholic mission church in Wynwood sits just north of the block that a Texas developer wants to redevelop. GALERIA DEL BARRIO But the Puerto Rican community that gave rise to the historic names is mostly a thing of the past. As the garment industry declined and disappeared, so did the garment workers who lived in the neighborhood. As it declined, Wynwood was plagued by crime, gangs and drug trafficking. In 1988, days of rioting ensued after undercover police bludgeoned a neighborhood drug dealer to death.Today, much of the population is a transient one, planners say. Over 80 percent of Wynwood Norte residents are renters, the association’s study says, though the population is trending younger. The neighborhood is dotted by vacant lots where houses were demolished; about 10 percent of Wynwood Norte is vacant land. Much of the remaining housing stock is deteriorated, though a few homes have been renovated in recent years by new owners moving into the area.Wynwood Norte residents today are among the city’s poorest. The median household income in the neighborhood is $19,800, and the median rent is $672, according to city of Miami planners. Fully a quarter of dwellings are officially designated affordable housing, including some public housing units, though some of it is not in good condition, the Plusurbia study says.Neighborhood businesses are faltering or disappearing. Dracula Video, for instance, long a mainstay on Northwest Second Avenue, moved out last year after the building that housed it was purchased, Vasquez said. Even the public schools are undersubscribed. Hartner Elementary and the Young Men’s Preparatory Academy are only at 50 percent capacity, planners say.Though there is plenty of low-cost housing, it’s in such bad shape that the neighborhood is attracting few families, Wernick said. That means it can’t capitalize on its status as one of Miami’s last largely residential zones in the urban core, he said.”It has remained very sleepy, but not in a way people are happy about,” he said. “There are lots of absentee landlords. Families that want to live in the neighborhood, they don’t have a lot of options. Professionals who want to live and work in the urban core don’t have a lot of options.” CAPPED HEIGHTThe Plusurbia plan would seek to foster compatible redevelopment through zoning tweaks to encourage incremental infill rather than large-scale projects, the typical Miami model. It calls for increasing allowable density while capping heights at four to five stories, and allowing developers extra square footage in exchange for payments into an affordable housing fund for the neighborhood.The plan also urges creation of a program of small grants to homeowners to underwrite repairs and renovations, and loosening of zoning rules to permit the addition of detached “in-law” quarters in single family home lots that allow for multi-generational living, or can be rented to boost family income and provide more affordable housing options.On the public side, the plan says the city and Miami-Dade must replace the neighborhood’s cracking sidewalks, improve street lighting and add to its thin tree canopy.The recommendations are the result of community consensus hammered out in public workshops, one-on-one meetings with local leaders, an online survey and walking tours of the neighborhood during which planners interviewed people on the street, said Plusurbia principal Juan Mullerat.“Everyone understood it needs to densify. Everyone was fearful additional density would displace them,” Mullerat said. “But overall we found there is room to grow within the neighborhood without displacing residents.“The whole idea here is that almost every recommendation is about mitigating displacement, increasing the affordable housing stock and supporting the existing residents.”One large problem that the plan would address, Mullerat said, is the suburban zoning assigned to Wynwood Norte by the city’s Miami 21 code, which does not allow sufficient density. The reason there is so much vacant land and little new housing in the area, he said, is that the rules make it unfeasible to develop there — a common problem in similar neighborhoods across the city, such as Little Havana.Those rules, Mullerat and other critics say, require too much parking onsite and too little building, making it almost impossible to physically fit it all in on a typical lot. That’s one reason why the typical Miami model of redevelopment is for an owner to amass multiple lots and build on a large scale, which displaces residents and helps drive up the cost of new housing.But that’s what’s likely in store for Wynwood Norte if the rules are not amended, Mullerat and Wernick argue.“If current conditions remain, doing nothing will lead to displacement, in my mind,” Wernick said.Yet Wynwood Norte already has the basics for success, stakeholders say. It is centrally located, dense, compact and eminently walkable, even if the sidewalks are cracking and the tree canopy thin. Social services, including a senior center, and Clemente Park are located on the business district main street. It’s a short stroll to Midtown Miami’s shops and restaurants and to Wynwood nightlife, both sources of jobs as well as diversion for residents.“It is because the location,” Vasquez said. “Wynwood is like a small little island, but there’s something always happening around it. Anybody that lives in Wynwood, you have everything at your fingertips. You don’t even need a car. You can take an Uber everywhere you need to go.”ARTISTS’ COLONYThe Bakehouse, meanwhile, has an ambitious plan that aims to turn it into a true community anchor.The center opened in 1986, after it was purchased by the city for an artists’ nonprofit to address a need for affordable working studios. At the time, artists were being pushed out of Coconut Grove by rising rents and redevelopment. Today, they’re being pushed out of the Wynwood arts district and downtown Miami.As Miami’s art scene grows, but affordable neighborhoods become increasingly rare, the need for housing for artists is a bigger need than ever, Leff said. The center is seeking zoning changes for its property to allow construction of up to 250 units of housing.Under a covenant signed when the city turned over the property, the bakery building must be preserved for artists’ use. So the development plan envisions a new residential building on the site, much of which is a parking lot or underused property, Leff said. The center expects to recruit investors or a developer to take on the housing portion, she said.The residential building would tie the Bakehouse more closely to the neighborhood, which would also benefit from the addition of hundreds of new residents to patronize businesses, Leff said.“We don’t want to overdevelop. Everybody recognizes the unique character of the neighborhood. We want to make sure whatever we do is in sync with the neighborhood,” Leff said.If the Wynwood Norte plan succeeds, Mullerat hopes it will become a new model for redevelopment in Miami — saving and enhancing what’s already there, instead of tearing it all down and building on a massive scale.“It’s been really a ground-up project. The neighbors have been very involved. It’s not developer-centric,” Mullerat said.“You are not going to do it tomorrow. We must create funding mechanisms that can fund all these lofty goals. It’s going to take time. But we need to start appreciating what we have.”

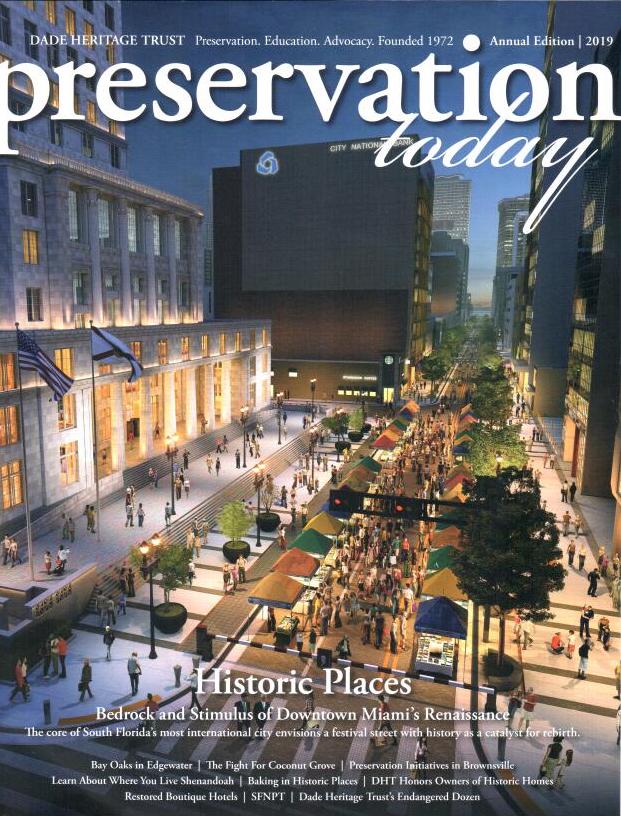

PlusUrbia's Megan McLaughlin contributed to the 2019 edition of Dade Heritage Trust Preservation Today Magazine.Her article is about the Vera Building, located in the OMNI Arts and Entertainment District of Miami. Read more about it below: Dade Heritage Trust was a key partner in the effort to create the Little Havana Me Importa Revitalization Plan. PlusUrbia is proud to collaborate with Dade Heritage Trust, helping to make Miami better, one step at a time.

Plusurbia Design was featured in the French magazine Urbanisme April, May, and June of 2019 issue. The article, written by Eric Firley, a Professor at the School of Architecture of The University of Miami, talkes about the City of Miami and its urban growth in spite of its battle with climate change. Plusurbia, along with other great firms in the City dedicated to urbanism, is mentioned for its groundbreaking work on the Wynwood Neighborhood Revitalization District, Little Havana Me Importa: Revitalization Master Plan, as well as the study of three Transit Oriented Development areas in Miami.

National Trust for Historic Preservation, PlusUrbia Design and local partners issue report with input from over 2,700 Little Havana residents and stakeholders.Miami (June 11, 2019) – With the goal of promoting the revitalization of the Little Havana neighborhood for current and future residents, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and PlusUrbia Design today released a master plan focused on building a healthy, equitable and resilient neighborhood community in Little Havana. The plan, put together over the course of more than two years and with the input of over 2,700 neighborhood residents and stakeholders and several local partners, brings together best practices and the latest thinking from a range of fields—from public health to urban planning to architectural design and historic preservation. It is the first plan of its kind to focus specifically on revitalizing and improving the quality of life for people in Miami’s most iconic neighborhood.The revitalization plan includes input from a collection of civic and non-profit organizations currently working in Little Havana, including: The Health Foundation of South Florida, Live Healthy Little Havana, Urban Health Partnerships and Dade Heritage Trust.From the time the National Trust named Little Havana a National Treasure in January of 2017, the Trust and its local partners led by Plusurbia Design, a local planning firm, have been focused on ways to retain the things that make this place one of America’s most beloved neighborhoods. While it is an iconic historic place, Little Havana is also a dynamic urban neighborhood whose residents face a range of challenges and threats, including poverty, sub-standard housing, displacement, poor transportation options and insufficient open space. This plan is an attempt to comprehensively address these challenges by bringing together an integrated set of national best practices from a diverse array of professional perspectives. Rather than a regulatory approach, the plan relies on increasing incentives, lowering barriers and respecting the existing heritage of Little Havana.“Little Havana is the heart and soul of Miami. It is also a longstanding symbol of the immigrant experience and one of the most essential places in America,” said Robert Nieweg, NTHP. “But there is no denying that this important place is also facing a range of threats, and its residents confront significant challenges on a daily basis, from sub-standard housing to poor transportation options to a lack of green space. In developing this plan, we listened to the concerns of thousands of local residents and stakeholders, and took advantage of the latest thinking in fields from public health to urban planning to architectural design and historic preservation to find solutions to these concerns. This is the first report of its kind, and webelieve it can be a road map for making life better for current and future Little Havanaresidents”"La Pequeña Habana is one of the best-known Latin-American barrios in the United States,"said Juan Mullerat, principal at PlusUrbia Design. "Though the neighborhood is one of Miami’spremier tourist destinations, those who spend time there know that its real value lies in itspeople and the legacies they have built over many generations in the neighborhood. This plan isinspired by the culture of Little Havana, and it seeks to ensure that this unique place and thepeople who created it will always have a home here." ABOUT THE NATIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATIONThe National Trust for Historic Preservation, a privately funded nonprofit organization, works to save America’s historic places. www.SavingPlaces.orgABOUT PLUSURBIA DESIGNPlusurbia Design is a Miami-based planning firm that designs contextual cities, towns and neighborhoodscollaboratively to create lasting value. www.plusurbia.comMEDIA CONTACTS: VIRGIL MCDILL, NATIONAL TRUST, 202.294.9187, VIRGILMCDILL@GMAIL.COMJUAN MULLERAT, PLUSURBIA DESIGN, 305.444.4850, JUAN@PLUSURBIA.COMRelated articles:WLRNhttps://www.wlrn.org/post/little-havana-revitalization-plan-released-will-now-go-actionThe Real Dealhttps://therealdeal.com/miami/2019/06/11/little-havana-could-be-redeveloped-like-wynwood/El Nuevo Heraldhttps://www.elnuevoherald.com/noticias/finanzas/acceso-miami/comunidades/article231432093.htmlWJCThttps://news.wjct.org/post/little-havana-revitalization-plan-released-will-now-go-actionCBS Miamihttps://miami.cbslocal.com/video/4102931-city-of-miami-unveils-plan-for-revitalization-of-little-havana/NBC Miamihttps://www.nbcmiami.com/on-air/as-seen-on/Mayor-Unveils-Plan-to-Revitalize-Little-Havana_Miami-511153152.htmlArchinecthttps://archinect.com/news/article/150141827/revitalization-plan-for-miami-s-little-havana-to-focus-on-more-affordable-housing-and-healthy-urban-livingCalle Ocho Newshttps://calleochonews.com/new-revitalization-plan-little-havana-me-importa/

BY ROB WILE AND JOEY FLECHASAPRIL 18, 2019 06:30 AMTri-Rail has yet to arrive at MiamiCentral Station, where Virgin/Brightline has long promised a downtown home for the stalwart commuter rail.But Tri-Rail continues to look ahead to stops that could serve rising populations along the way. A new study commissioned by the public rail company recommends potential local train stops in two Miami neighborhoods: Midtown and Little River.Coral Gables-based Plusurbia Design authored the report, which evaluates two spots in the Midtown corridor as suitable locations for a train platform in the near future, with some caveats. The planners wrote that any train stops must come with broader upgrades along surrounding streets, including redone sidewalks, better lighting and safer crosswalks, to encourage people to walk to the platforms.“You can put a station anywhere,” said Plusurbia principal Juan Mullerat. “But if you make it unpleasant to get there, then it will fail.” The study proposes a new train hub in Little River further in the future, with redeveloped residential and commercial buildings surrounding a station, all carefully planned with significant public input and sensitivity to residents who wish to stay in a gentrifying neighborhood.The report offers a vision of what transit-hungry citizens clamor for: connections that allow people to ditch cars and easily move between downtown and some of Miami’s most well-known neighborhoods.The business side of the idea is the tricky part. Plans for these train stops are contingent upon Tri-Rail’s access to tracks owned by Brightline, a private transit company. Planning from the two entities have moved at a pace Miamians have come to expect from big-picture mass transit projects: The date for Tri-Rail’s debut at MiamiCentral station, once expected in 2017, has been pushed back several times.A representative for Tri-Rail said there is now no projected date for when its first train will pull into downtown Miami. But in response to questions from the Miami Herald, a Brightline spokesman said it is working to install required safety controls for Tri-Rail to use its tracks, and is aiming to finish the work before the end of 2020.Still, politicians and local businesspeople endorse Tri-Rail’s idea. Last year, the Transportation Planning Organization — a countywide government agency that approves federally required plans and transportation policies — agreed to pay half the cost of smaller-scale pilot projects across Miami-Dade that would demonstrate people’s appetite for mass transit along corridors outlined by the countywide transportation blueprint known as the SMART Plan. Cities with the projects would pay the other 50 percent. Among those projects: A temporary train platform somewhere in the area of Midtown or the Design District.Miami Mayor Francis Suarez said that regardless of the operator, there’s an urgent need for traffic relief along the increasingly congested Biscayne corridor.“From a public policy perspective, from a quality of life perspective, it’s really important that this get resolved,” he said. “We cannot let this asset go underutilized.”Plusurbia’s report highlights two potential Midtown locations that could work for a train platform, if some significant changes were made — on the north end, bordering the Design District under the I-195 overpass, or further south, between Northeast 29th and 27th streets. Planners believe both would have a built-in ridership from the growing number of residential and commercial developments in Midtown, Wynwood, Edgewater and the Design District — along with the people from downtown and further north who wish to visit the area. The plan suggests there are fewer obstacles for a permanent platform south of 29th Street than under the I-195 overpass. The overpass site is north of Northeast 36th Street near a five-point intersection with Federal Highway and Northeast Second Avenue — the site of daily rush hour traffic snarls. The space on either side of the tracks between 27th and 29th streets would require the government to either acquire land or work with property owners to develop a station.One of those owners is interested. Bill Rammos, who’s invested in the Miller Machinery & Supply warehouse at 127 NE 27th St., told the Miami Herald he would be open to adapting the “old, underdeveloped warehouse” into a train station with commercial space.“I think that would help the whole neighborhood,” he said.Rammos considers the report a confirmation of what he sees every day: a growing community with new and obvious needs for those who live there, as well as people visiting the area — and cars are not the long-term solution.“More parking lots and garages for more cars ... we’ve been doing that for years,” he said. “And it’s not working.”For the temporary platform being pursued by the city of Miami, municipal planners still prefer the site north of 36th Street because the city’s parking authority already has land leased from the Florida Department of Transportation.“The report concludes that based on potential ridership, number of residents, and concentration of jobs, a location between Northeast 27th and 29th could better support a train station and would be better served by a train station than a location near 36th Street,” said city spokeswoman Stephanie Severino. “However, the specific station location near 29th would require land acquisition and there is not currently parking on-site.”.Plusurbia’s recommendations could guide the selection of a site for both a temporary and permanent platform, Severino said.Farther north and further into the future, the urban planning firm deemed a strip of land along Little River just north of Northeast 79th Street a viable home for a train stop accessible to residents of Little Haiti, Palm Grove, the Upper Eastside and Shorecrest. Planners see the potential for a transit hub, which could include a redevelopment of the Midpoint shopping center with new commercial and residential space, that balances gentrification already in motion with keeping current Little Haiti residents and the fabric of their neighborhood intact.The report emphasizes that maintaining the area’s cultural character and scale is crucial in a part of Miami already under pressure from developers, a point underscored by a current controversy about a large planned development about 17 blocks south of 79th Street. Plans for the massive Magic City Innovation District have fueled an intense debate among Little Haiti activists who agree the roughly 18-acre project would forever transform Little Haiti but not whether that change would be for better or for worse. Another 22-acre redevelopment proposal on Northeast 54th Street stalled last summer when activists objected.The need for reliable public transportation would likely have broad community support, though, as long as it does not come with real estate projects that would displace longstanding residents, the activists said. Meaningful community input would be key.“Any effort to relieve traffic that will not intrude on people’s way of life would be welcome,” said Marleine Bastien, a longtime area activist and director of the Family Action Network Movement.Last year, Northeast 76th Street resident Alisa Cepeda told the Herald she thought administrators ought to consider a train stop within walking distance of her neighborhood. With a station at 79th Street, she’d be able to make the seven-mile commute to work on just one train and a half-mile walk from MiamiCentral to her job on West Flagler Street. She’d have a much simpler commute than her current public transportation option of transferring from a trolley to a Metrobus to the Metromover to get to Government Center.A Metrorail passenger train rolls by the Brightline terminal in downtown Miami in March. Jose A. IglesiasJIGLESIAS@ELNUEVOHERALD.COM“I think it’s an absolutely wonderful idea,” she said Tuesday.It’s not a new idea, but the process to build a train platform is complicated by the ownership of the tracks, which forces public agencies to negotiate access to private infrastructure.Florida East Coast Industries (the parent company of Brightline, which is being renamed Virgin Trains USA) owns the tracks that Tri-Rail, operated by a public tri-county transit authority, wants to use. Tri-Rail was supposed to have arrived at MiamiCentral by 2017, according to one of the earliest presentations Tri-Rail published showing both Brightline (then All Aboard Florida) and Coastal Link projects.Today, Tri-Rail executive director Steven Abrams says Tri-Rail and Brightline have a “cooperative, complementary relationship.”“We really serve different residents in South Florida,” he said. “Our service is very much for the daily commuter. We stop every two miles along our route in various cities, we have a lower price point on our ticket. Whereas Brightline, it’s three stops, it’s more geared toward the tourist or businessperson in the area.”While there is some overlap, one that would increase as Tri-Rail serves as a conduit for Brightline passengers, “coexisting is fine.”“They made it possible for us to go into MiamiCentral Station by reserving a platform and working cooperatively with us,” he said. “They think the same of us. If you asked, they have a cooperative relationship with Tri-Rail.”Yet the opportunity is huge.“We would grow tremendously if we were able to extend our existing service through downtowns of major coastal cities,” he said.Aileen Boucle, executive director of Miami-Dade’s Transportation Planning Organization, said the goal has remained for Tri-Rail riders to have another stop before downtown on the day the train first pulls into MiamiCentral, even if it’s a temporary location while a permanent station is planned.“Having that service would allow residents and commuters to benefit from that project immediately,” she said.For Suarez, one of several Miami-Dade municipal politicians who sit on the planning organization’s board, at least a stop in the Midtown/Wynwood/Design District is necessary today — so much so that he thinks a temporary platform should be built wherever most feasible in the short term to demonstrate the potential ridership.“I’d rather have something to start proving the concept now than wait for something permanent,” he said.A Tri-Rail train heads north from the Northwest 79th Street station in Miami-Dade. C.M. GUERREROEL NUEVO HERALDRead more here: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/article229002739.html#storylink=cpy

Miami's Shenandoah: a neighborhood ahead of its timePlusUrbia is excited to be working to survey the Shenandoah neighborhood along with Dade Heritage Trust.POSTED ON MARCH 21, 2019 AT 1:18 PM.WRITTEN BY THE NEW TROPIC CREATIVE STUDIOA look at the 1800 block of SW 11th Terrace between 1920-1930 in the Shenandoah neighborhood of Miami. (Photo by Gleason Romer)WHAT IT IS: Shenandoah, a neighborhood just southwest of downtown Miami, is one largest collections of 1920s and 1930s architecture that the city or state hasn’t studied or documented.Megan McLaughlin moved to the neighborhood 10 years ago because she exhausted of her 90 minute commute to downtown. With two toddlers, she felt like she was missing out on so much time with them. So she and her husband moved to Shenandoah, where they can walk everywhere and catch a bus to downtown.McLaughlin and Chris Rupp from the Dade Heritage Trust have partnered to survey the neighborhood and put together a report with the data they collect. With a grant from the state, they’ll create a file for each of the 650 properties in Shenandoah that will include the history of the house, previous owners and residents, and the prominent architectural features.MOST SURPRISING FACT: According to McLaughlin, Shenandoah is one of the most diverse neighborhoods in Miami, a city that’s already very inclusive of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds. McLaughlin said that city directories show that the neighborhood was at some point home to Jewish, Middle Eastern, and Russian families. Cuban and other refugee families also settled there in the 1960s.WHY IT IS IMPORTANT: Shenandoah was one of the first suburban developments outside of downtown and has always been ahead of its time, McLaughlin said.“It was different from Coral Gables and Miami Shores and some of these other maybe more known suburbs because it was diverse from the beginning,” she said. “You had already a mix of duplexes, houses, little apartment buildings, corner stores, all of these things that I think the new urbanism and other planning folk talk about that now as the gold standard of a ‘good urban neighborhood’ but Shenandoah had it 100 years ago.”HOW TO GET INVOLVED: If you’re interested in volunteering to help conduct the survey or organize the collected data – or organize a similar survey for your own neighborhood – McLaughlin said you can contact the Dade Heritage Trust.Find out more information by reading the article written by THE NEW TROPIC CREATIVE STUDIO through the link below:https://thenewtropic.com/neighborhood-spotlight-working-to-document-shenandoahs-historic-architecture/

We use cookies

We use our own and third-party cookies to be able to correctly offer you all the functionalities of the website for analytical purposes. You can accept all cookies by clicking "Accept cookies", obtain more information in our

Website Policyor configure/reject their use by clicking on Settings".

Accept cookies

SettingsBasic cookie informationConfirm preferences

This website uses cookies and/or similar technologies that store and retrieve information when you browse. In general, these technologies can serve very different purposes, such as, for example, recognizing you as a user, obtaining information about your browsing habits or customizing the way in which the content is displayed. The specific uses we make of these technologies are described below. By default, all cookies are disabled, except for the technical ones, which are necessary for the website to work. If you wish to expand the information or exercise your data protection rights, you can consult our Website Policy.

Accept cookiesManage preferencesTechnical and/or necessary cookies

Always active

Technical cookies are those that facilitate user navigation and the use of the different options or services offered by the web such as identifying the session, allowing access to certain areas, filling in forms, storing language preferences, security, facilitating functionalities. (videos, social networks…).

Analytic Cookies

Analysis cookies are those used to carry out anonymous analysis of the behavior of web users and that allow user activity to be measured and navigation profiles to be created with the objective of improving websites.