February 20, 2020

Each December, the art world descends on Miami Beach for Art Basel’s American installment, Design Miami. In late 2018, Cuban-American artist Xavier Cortada wanted to loop a social statement into the cresting euphoria.

Cortada created blue and green yard signs; each listed a number, designating how many feet of sea level rise would submerge a given property in his Pinecrest Gardens neighborhood. He incorporated designs from “Ice Paintings,” an artwork he had completed in Antarctica that was composed of sediment from melting glaciers.

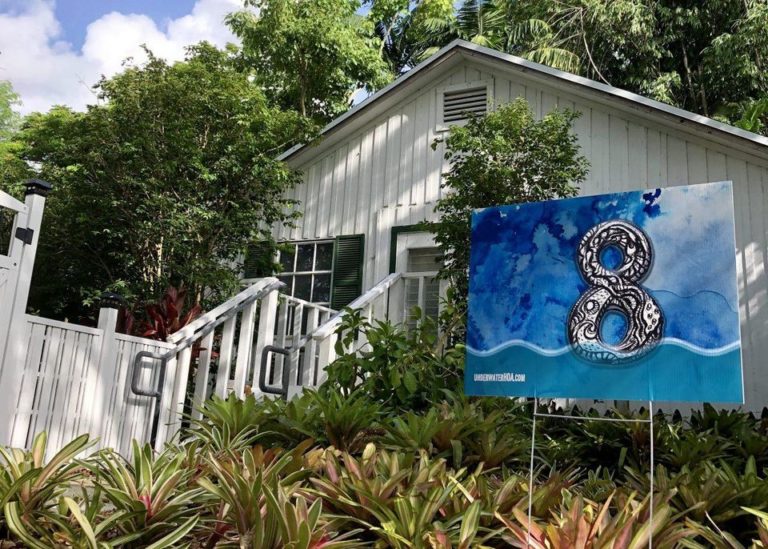

Artist Xavier Cortada’s studio in Pinecrest, with an “Underwater HOA” sign indicating how much sea rise will submerge the property

Cortada and his neighbors staked these signs in their front yards, and with that, his

Underwater HOA project punctuated Design Miami with a reminder of looming danger. “By mapping the crisis to come, I make the invisible visible,” Cortada says. “Block by block, house by house, neighbor by neighbor, I want to make the future impact of sea level rise something no longer possible to ignore.”

Among American cities, Miami emerges as a particular case study in how and where we will house people as climate pressures mount. Its famous beaches and waterfront condominiums will struggle with sea level rise in the next 50 years—and inland regions will feel pressure, too, as coastal residents search for dry ground. Already, salt water routinely floods Miami’s streets and bubbles up in family yards, permeating the porous limestone bedrock deep underground. While basements and garages flood, developers proceed headfirst into seaside condo projects.

As temperatures, oceans, and anxieties rise, might designers help anticipate—and adapt to—what is now considered the inevitable? In Miami and Miami Beach, what will happen to neighborhoods, like Cortada’s, expected to be underwater within their residents’ lifetimes? Can new buildings, and new strategies, emerge from competing dialogues?

Stoked by this dilemma, Harvard Graduate School of Design professors

Eric Höweler, an architect, and

Corey Zehngebot, an urban designer and architect, organized a GSD investigation into issues of housing, resilience, and adaptability, using Miami as an urban laboratory. Their investigation, the Fall 2019 option studio “Adapting Miami: Housing on the Transect,” engaged a cohort of 12 GSD students in months of research, site visits, and critical review.

Students generated housing-focused proposals that offer a portrait of Miami’s risks and opportunities. They collaborated with and drew research insights from a concurrent seminar led by

Jesse M. Keenan, recognized as a leading researcher on questions of climate and real estate; he has worked to shape a global discourse on the relationship between climate change, social equity, and applied economics.

The geographical and conceptual heart of their study is a periscopic transect of the city created by two of Miami’s most iconic streets—Flagler Street to the north, and 8th Street, also known as Calle Ocho and the Tamiami Trail, to the south—which bracket a swath of Miami’s fabric, cutting westward from the City of Miami’s high-density eastern coastline, through Little Havana, West Miami, and Tamiami, and into the Florida Everglades. This transect captures a range of natural ecosystems and urban conditions while representing the constraints of Miami’s built and natural environments: hard boundaries of high-density urban development at some edges (east, north, and south) and water everywhere else—the Everglades to the west, the Atlantic to the east.

It is along and between these corridors where interesting opportunities for different housing typologies emerge, opportunities that are intertwined with mobility, streetscape design, density, infrastructure, ecology, resiliency, and adaptation, Zehngebot observes.

For the studio’s December 2019 final review, participants organized their projects along a model of the full Flagler/Calle Ocho transect

“We are invoking the transect in order to provoke a concept rooted in the New Urbanist ideology of Andreas Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zybek, whose firm is appropriately based in Miami,” Zehngebot says. “We are appropriating the transect from the New Urbanists just as they appropriated it from ecology and environmental planning because it is a useful framework for understanding the transition from urban to rural and how might housing typologies manifest themselves at different moments or zones along a streetscape continuum. This is further complicated in Miami, a city that feels the effects of water from all sides, and whose areas further from the coast are counterintuitively more vulnerable where the water is coming not from the sea, but from the ground.”

With the constraints of space and time, and the limits of human and financial resources, where might there be opportunities to rethink how we plan the buildings, cities, and regions of the future?

An American City’s Formative Years: The Legacy of the AutomobileAs American cities go, Miami is young. The City of Miami was officially incorporated in 1896 and named for the Miami River—derived, in turn, from

Mayaimi, the historic name of Lake Okeechobee and the Native Americans who had lived in the region for centuries. So-called lot-and-block development took hold of the city’s early planning, with civic infrastructure like transit and public space an afterthought.

Despite its youth, Miami is a city with an organic relationship to change—natural, political, and otherwise. The city’s tradition is to live on or with water, and with nature. As the seas ebb and flow, so does Miami’s urban rhythm.

But today, Miami’s freedom to change is increasingly constrained. It is arguably one of the few cities in the United States with a truly limited supply of land. Its 1920s-era “garden cities,” like Coral Gables, began percolating along the eastern shore and spread westward, growing more densely packed as they approached the Everglades. Now, out of necessity, the city is looking to move eastward back toward the sea, infilling its limited land with higher-density housing.

With a renewed interest in fitting as many people as possible on limited land, many Miamians are realizing that the city’s traditional housing forms may no longer be sufficient. The single-family, low-rise house that dominates Miami’s urban fabric—a herald of the “American Dream”—may fail to sustain successive waves of younger, more transient citizens and new, expanded forms of family. Meanwhile, the high-rise towers that stand along the shoreline will be exposed to rising seas and stronger, more frequent storms. The modernist, Art Deco styles that flavor the city with clean, simple geometries don’t lend themselves to climate-resilient architecture, either.

Compounding these pressures is the city’s lack of cohesive, holistic city planning. Miami offers a mix of vibrant, diverse communities, but they have competing municipal priorities and policies.

Then there’s the legacy of the car. As Miami matured into the 1900s and the so-called era of the automobile, the car shaped the city’s spatial dimensions: long, straight avenues and single-family houses with driveways. One result is that rather than an urban center with spokes and connective tissues, Miami’s urban design resembles a large city composed of multiple, smaller cities—a sort of architectural accident.

“Miami didn’t have the chance to develop without the impact of the automobile,” says Juan Mullerat, founder and director of urban design firm PlusUrbia. Among the projects that Mullerat and PlusUrbia have developed are Miami’s Little Havana Revitalization Master Plan and Transit Oriented Development (TOD) Guidelines for the City of Miami. The firm’s work on Miami’s Wynwood Neighborhood Revitalization District earned the American Planning Association’s 2015 America’s Great Places Award.

Overlooking a lush Little Havana tree canopy from PlusUrbia’s offices, Mullerat explains to the GSD studio that, in his native Spain and throughout Europe, cars and parking are considered amenities, like a swimming pool, rather than standard elements. When you allot less space for cars, he continues, you get more space for people. “The neighborhood itself becomes the amenity,” he says.

As Mullerat guides the studio through neighboring Little Havana, MArch candidate Aria Griffin pays attention to a series of hulking parking garages, standing like monuments to a car-centric history—unavoidable, but also largely unused. She’s wondering if residents might benefit from something other than parking.

Griffin’s concurrent research on medical care had led her to the conclusion that, in essence, hospitals are the most expensive form of housing in the nation. She turned this equation into opportunity by proposing a mid-rise tower, containing both housing and a hospital, at the corner of 12th Avenue and Flagler Street in East Little Havana. Griffin proposes replacing the currently existing Walgreens with the tower, also modifying the current on-grade, covered parking lot surrounding the store in order to generate a friendlier streetscape.

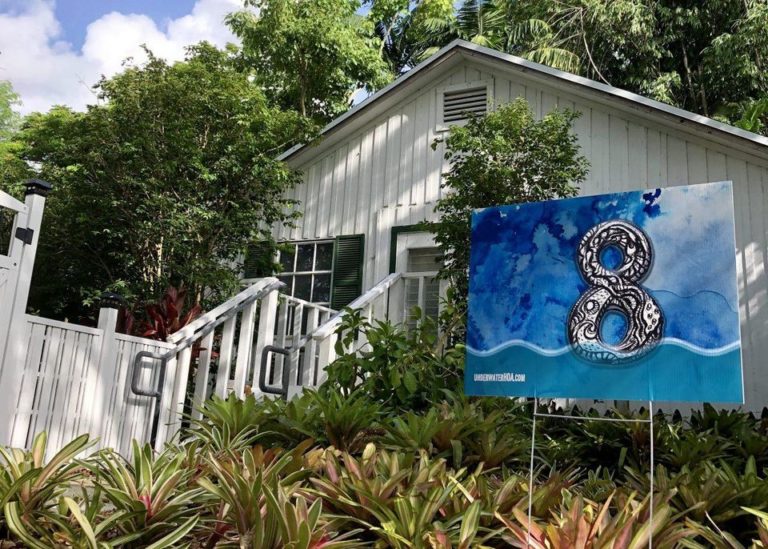

Final model of Aria Griffin’s proposed project

Griffin’s project would work to combat issues of loneliness and disenfranchisement in addition to promoting healthier living for those most at-risk ahead of the climate disasters expected to loom in Miami’s future: the elderly, the disabled, and the homeless.

“I knew I wanted to propose a project that would provide housing, integrated health services, as well as public space to East Little Havana,” Griffin says. “I believe that such institutions must be integrated in the city’s fabric to better serve its communities.”

Griffin observed other considerations at play. Building inland helps defray flood risk—a theme observed throughout the studio’s investigation—while the character of East Little Havana, marked by a lively streetscape and vibrant community life, makes it appealing for residents. She also addressed questions of mobility and accessibility issues. Rather than densifying the entire Calle Ocho corridor with a transit line, she instead prioritized nodal transit connections that would improve circulation.

Mullerat and Griffin chat during the studio’s final review, December 2019

Westward down the transect, MArch candidate Don O’Keefe saw a similar opportunity locked within the Florida International University (FIU) campus. Three large parking decks greet visitors at FIU’s main entrance. By replacing these with low-rise but high-density housing, O’Keefe aims to transform FIU into a transit- and pedestrian-oriented community in which student housing, classrooms, and public space is intermingled.

As Griffin seeks to integrate medical infrastructure with housing—literally and conceptually—O’Keefe sees a parallel opportunity with higher education, a staple of Miami’s economy. O’Keefe’s project also anticipates coming storms, with housing designed to be adaptable: classroom and public spaces allow for the expansion of FIU’s existing so-called “Living Learning Community” scheme. Meanwhile, common areas within the dorms could be flexibly rearranged and partitioned for use as overflow housing for nearby residents in the case of disaster, expanding FIU’s existing policy on neighborhood assistance during major storms.

O’Keefe’s master plan shows one stage in the campus development. New buildings shield the massive existing parking deck from surrounding neighborhood and establish a new pedestrian oriented street grid.

Removing parking, though, reignites long-standing questions over mobility and accessibility, especially for aging populations. The East Little Havana intersection of Calle Ocho and Flagler Street offers a snapshot: it throbs with commercial activity, but to get there, pedestrians need to cross the wide, constantly trafficked Seventh Avenue, a vestige of Miami’s car-centric urban design. Instead, Höweler asks the studio, could Flagler emerge as a transit corridor, facilitating urban nodal connections and opening Little Havana to greater mobility and connectivity?

Don O’Keefe discusses the research behind his FIU proposal during the studio’s final review, December 2019

This question speaks to how space and typology interact: why start at the scale of the house and scale upward from there instead of planning larger, more connective institutions or infrastructures first and embedding housing within? How does the urban fabric respond when cities and regions invert the scale at which they design?

In Miami, questions like these intersect where so much of the city finds inspiration: at the water.

Living with, and on, WaterMiami’s tropical climate invites comparison to cities like Bangkok and Singapore, where high-density buildings sit beside broad, rainforest-like public spaces. Accordingly, throughout Miami’s urban growth, buildings have been spaced far enough apart to enable air circulation between plots.

Extra space around buildings, though, means less collective space for public commons—and today Miami, like many American cities, is renewing its interest in public space. A trio of GSD students saw Miami’s city waterfront, where the Miami River meets Biscayne Bay, as an opportunity to add public space at the water.

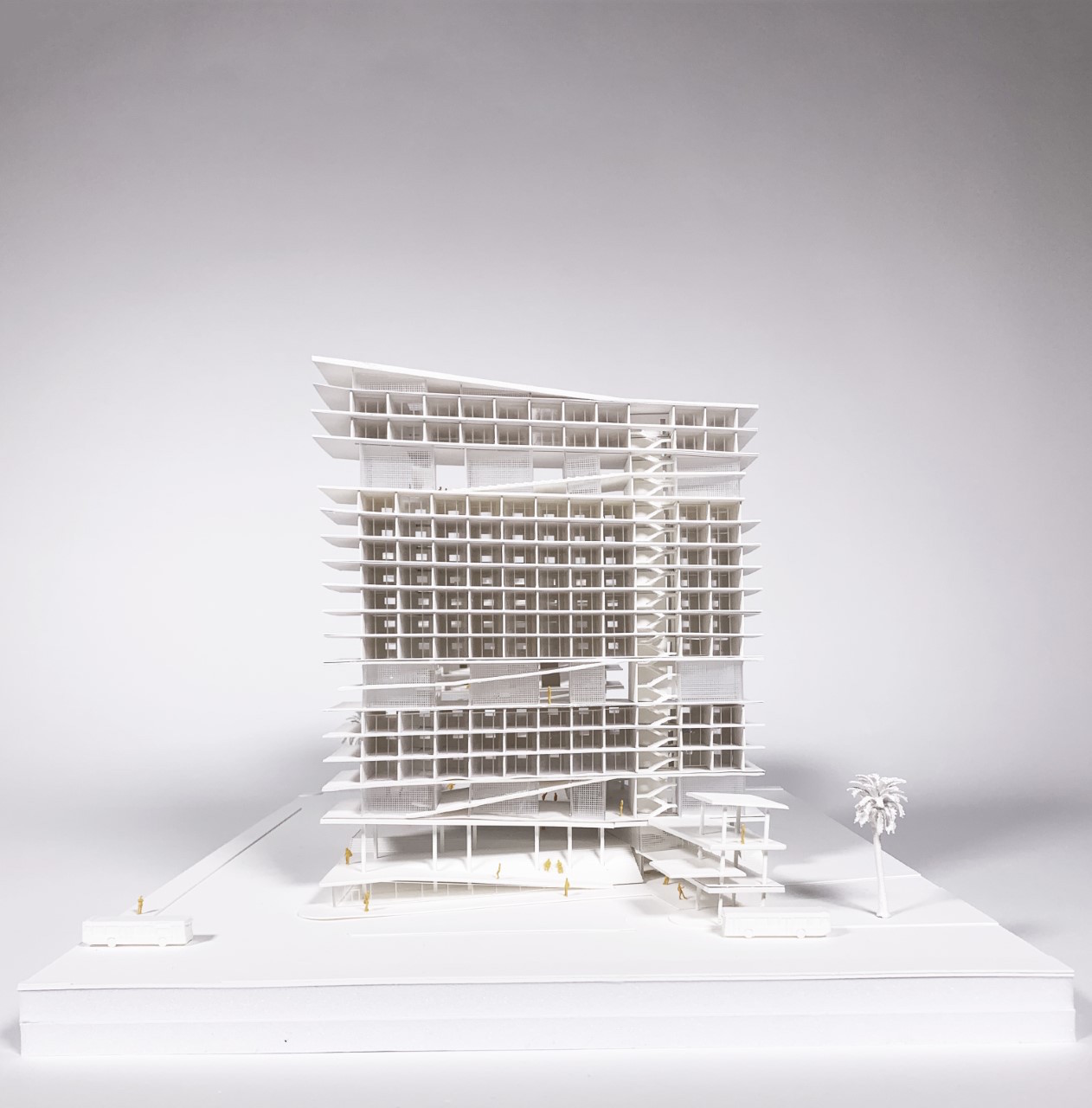

With their proposal, “Loop Within,” Adam Jichao Sun, Pengcheng Sun, and Shunfan Zheng pursued the chance to connect Miami more with nature, and to symbolically and literally unify water with people. They also wanted to experiment with the concept of a “vertical city,” extending the concept of high-rise towers into a more urbane and public, rather than cloistered, experience.

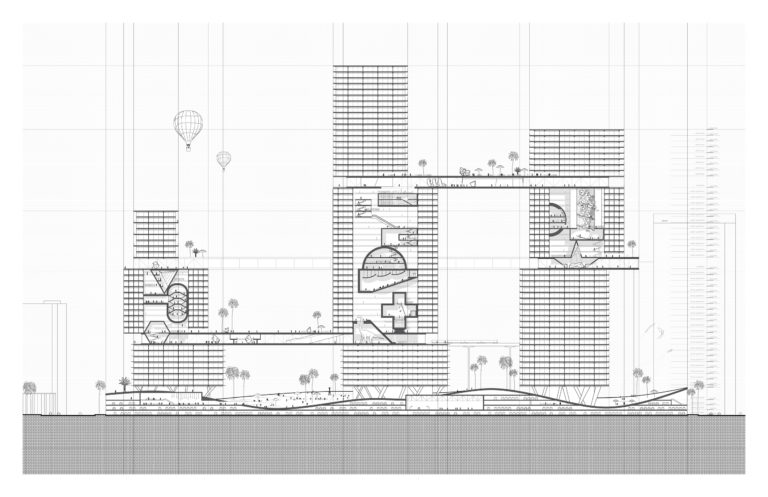

“Loop Within” presents three high-rise towers on top of an undulating podium, with a single, publicly accessible walkway connecting the towers at varying heights, forming a continuous physical loop within the building. The walkway would be accessed by an oblique elevator facing the Miami River waterfront, as well as an elevated railway station at the project’s podium platform. The platform itself, with its physical ebbs and flows, navigates people from the river walk upward toward cultural and other public programming within the towers.

Section plan for “Loop Within”

The proposal’s connectivity works at the master-plan scale as well. Rather than an enclave-type development, “Loop Within” bridges what are currently segmented city blocks to generate a connected river-walk experience. Cultural programming is distributed at nodes along the waterfront in the interest of creating a

destination out of the waterfront.

“Articulated as a cultural loop, our proposal emphasizes physical accessibility and visual attraction to the urban context,” the team writes. “The juxtaposition of public and private development, as well as a broad spectrum of dwelling units, renders the super-block into a ‘city within one building’ concept.”

The team also sensed the needs that building projects in Miami must resolve—namely, limited housing and rising seas. “Loop Within” fills the bulk of its towers’ interiors with housing, while the walkway’s physical infrastructure includes a seawall to mitigate flood risk.

Juan Mullerat interrogates “Loop Within” during the studio’s final review, December 2019

“Loop Within” stands as a bit of a metaphor for Miami today: incorporating both people and water, it synthesizes questions of economics, culture, and the risks of the future, pulling them together in new ways to make or suggest new forms of city-making. With a sense of temporality and adaptability baked into the design, the project both represents and responds to the city’s relationship with change. It also pivots away from the possessive, land-centric model of previous real estate development.

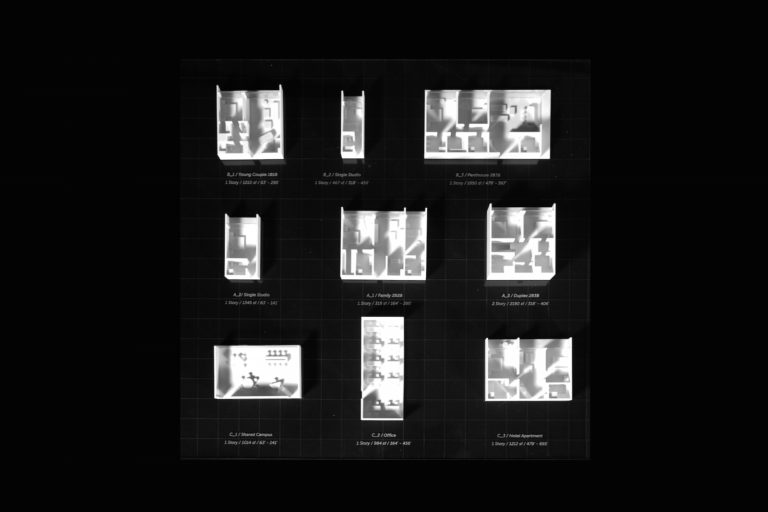

“Loop Within” would offer a spectrum of housing-unit types

“The project’s dynamic relationship with water is largely achieved by articulating its podium as one undulating typography with programmatic flexibility under different water height conditions,” the team observes. “The undulating surface presents a welcome gesture to the potential sea-level rise and unveils different modes of flow: flow of water, and flow of people. Both the existing multi-ground-level condition and the potential sea-level rise spontaneously render the feasibility of a ‘vertical city’ that dynamically interacts with the water.”

Colleague Yuebin Dong, an MAUD candidate, offered a complementary project that would extend this symbolism further: a school on the water. Currently existing KLA Kindergarten and Elementary School, near Brickell City Center, has been threatened with demolition; in maintaining its physical presence, Dong advocated for civic democracy, prioritizing education among the various features of Miami’s iconic waterfront while also building in spaces that could double as public amenities, like a library or a gymnasium.

Water presents opportunity in Miami, but also threat—and inland regions will feel the pressure, too.

MArch candidate Grace Chee followed the transect to its Everglades terminus, arguing that development into the Everglades is inevitable in the near future, as suggested by the proposed expansion of the Urban Development Boundary in Miami-Dade’s 2020/30 Land Use Plan. Her proposal, “Sub-Urbia,” proposes an environmentally responsible model of housing development that minimizes disruption to the natural ecology and explores the implications of living in a state of both suspension and floatation. She drew design inspiration from traditional housing in the Mekong floating villages of Vietnam, seeking to replicate the complex and ephemeral relationships between different housing types within the village, with varying degrees of permanence and attachment to land.

“With its daily and seasonal tidal fluctuations, the marshland provides an opportunity to create a prototype for amphibious living in Miami in response to rising sea levels, one that also offers an alternative suburbia to that which lies on the other side of the UBD,” Chee writes.

Fellow MArch candidate Kofi Akakpo brought a similarly critical eye to the relatively inefficient land usage of cemeteries, especially those located in urban cores where land is at an increasingly high premium. Thus, Akakpo’s studio proposal, “Can the Living Live with the Dead?,” reinvents the horizontal cemetery as vertical, a phenomenon already happening in countries like Brazil and India. With this reinvention, Akakpo asks another vital, if macabre, question: with cemeteries and other burial grounds, what happens to all of those bodies as water creeps inland?

“Aside from the inefficient use of land that is ground burial in traditional cemeteries, as flood waters come and ground waters rise with the sea-level, we run the risk of a lot dead bodies, particularly from old caskets, siting within the water table, contaminating ground water sources,” Akakpo writes. “A lot of these bodies will have to be moved to protect our fresh water sources.” It’s an observation that gets at some of the less-obvious but unquestionably threatening impacts of rising waters.

A view across the retaining pond of Akakpo’s proposal

Akakpo’s project would deliver a ring of housing, centered by publicly accessible green space and adjacent to a grid of vertical ossuaries into which bodies would be relocated from underground burial plots. A retaining pond at the middle of the ossuaries would provide both a slice of visual beauty, as well as a floodwater safety valve.

Akakpo’s proposal highlights the reality that water may prove unstoppable, its march inland carries various layers of risk, and our waterfronts are hardly the only consideration at stake.

Art as InstigatorIf Miami is shaped by water, it is fueled by art.

Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood looks a lot more colorful, and welcomes many more visitors, than it did a decade ago. Abandoned lots and buildings have been transformed into a sort of ever-evolving outdoor museum, with masterfully designed graffiti art covering almost every available surface. Funky dining spots and retail shops have sprung up. Some would say Wynwood actually feels like a

neighborhood. Its transformation started with little more than creativity and paint.

Srebnick guides the studio around Wynwood Walls during the studio’s September 2019 Miami visit

“Art is energizing, it creates a sense of place, and it brings people together,” says Jessica Goldman Srebnick as she guides the GSD studio through Wynwood Walls. Srebnick is founder and CEO of Goldman Global Arts, which operates Wynwood Walls; her father, Tony Goldman, collaborated with art curator Jeffrey Deitch to spark Wynwood Walls in 2009. In recent years, Srebnick started inviting graffiti artists from around the world—many of them never before exhibited—to color Wynwood, literally and otherwise.

As Srebnick worked to make Wynwood a new Miami destination, businesses started paying attention. She turned down Starbucks and 7-Eleven and, instead, kept looking for talent from around the world who might want to bring their slice of creativity to Miami. Today, Srebnick and Goldman Global Arts welcome millions of visitors to Wynwood Walls each year, free of charge.

Wynwood Walls. [Photo by BonzoESCFollow_. Available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0)]

The result is a neighborhood where, Srebnick says, you can feel a sense of place, not unlike New York’s SoHo or Los Angeles’s Arts District. “You see a lot of people wandering around Wynwood now,” Srebnick observes. “Art has made the neighborhood itself an amenity.” She adds that not a single Miami resident has been displaced in the process.

Historically, Miami has lacked a single, unified cultural district, though the city’s cultural and artistic production is globally renowned. Streams of intense creative production and spirit thread through the city, and individuals like Srebnick have established their own sorts of pocket districts, which in turn attract business and cultural attention. It’s a pattern that jibes with the city’s generally laissez-faire, homegrown attitude toward city development.

A few blocks north of Wynwood Walls, the Bakehouse Art Complex hums with a quiet focus. Bakehouse was founded by and for artists in 1986 and, with support from the City of Miami and Miami Dade County, transformed an industrial, Art Deco–era bakery in a then-blighted neighborhood into a home for talented artists, helping address the difficulty of finding space for creating and developing a practice.

Now, more than 30 years later, Bakehouse is trying to maximize use of its 2.3-acre campus in the heart of Miami’s urban core to address the city’s affordability crisis, says acting director Cathy Leff. As a result of the organization’s access to and engagement with its community of artists, city officials, and surrounding neighborhood—as well as with Harvard GSD’s ongoing “

Future of the American City” initiative—the organization is on a path to rezone its site to be able to add residential uses, specifically affordable housing for artists, Leff says.

“If successful, Bakehouse can become a true cultural anchor in a multigenerational and multicultural community, embedded in and embraced by the community to become a more robust and public commons for critical discourse, community dialogue, and exchange,” Leff observes.

MArch candidate Brian Lee saw such opportunity with the famed Miami–Dade County Auditorium, at the corner of West Flagler Street and 27th Avenue. Opened in 1951, the auditorium’s architecture shouts Art Deco revival, while the surrounding neighborhood bears vestiges of an automobile era: a relentlessly square grid that serves cars but complicates connectivity among the area’s art and cultural destinations and transit options. Lee saw an opportunity for greater neighborhood connectivity as well as higher-density housing.

Presentation model of Brian Lee’s proposal

Lee proposed a new theater to replace the auditorium after its lifespan, with a cap on parking spaces and a diagonal-cutting route that connects much of the area’s neighborhood development with local rapid-transit nodes. Housing would be integrated with Lee’s new auditorium, creating a courtyard that would double as an outdoor lobby.

“More often than not, such multi-use developments are broken into their component parts, each of which is stacked or separated into large podium-tower configurations or segregated buildings,” Lee observes. “My project tries to challenge these types, by attempting to integrate the programs more closely so that residents can participate in this larger performance.”

Brian Lee presents his reimagined Miami-Dade County Auditorium during the studio’s final review, December 2019

In today’s Miami, art can offer a foundation, a catalyst, and a sustaining force for housing and sense of place. But art has also played the role of activist: the Bakehouse rose from the need to offer sustainable living for artists and their practices, while cultural institutions like Miami’s Knight Foundation have worked for decades to convene dialogue and programming that stirs debate and tackles urgent social and political issues. (Knight was founded by newspapermen seeking new ways to communicate and thus to stoke public awareness; as Knight’s Victoria Rogers observed during a panel discussion at Bakehouse, “engaged communities have always been critical to democracy.”)

In parallel, themes of climate change and rising seas have permeated the Miami art world—as the activism of Cortada’s

Underwater HOA exemplifies. Artists and designers like Cortada have emerged as powerful communicators to herald the urgency and possible solutions around Miami’s issues. With so many of the city’s famed institutions perched on the water, art, climate, and dialogue work together in a circular feedback loop, each informing and driving the others.

The Immigrant Experience and the “New American Dream”In considering Miami’s waterfront as a democratic space, studio members emphasized a stitching together of segmented blocks. Indeed, throughout much of Miami’s urban fabric, segmentation and separation appear as rules—perhaps another vestige of the tropical-climate planning that favored spacing and subsequent air circulation, or more broadly of the city’s lack of holistic urban planning.

Regardless of cause, one effect of physical segmentation is social and community isolation. Single-family homes and high-rise towers alike are generally private experiences with private or individual entrances, and lack of public spaces compounds this effect.

For waves of immigrants and other newcomers, this urban fabric is hardly welcoming. Hua Tian and Jungeun Goo, both candidates for the MArch in Urban Design, and Haey Ma, an MLA candidate, saw this as a stimulus for a typology refresh.

Tian’s “A Piece of Life: Collective Housing for New Immigrants” takes up the intersection of 8th Street and 12th Avenue. Marked by lively street life, authentic human interaction, and nearby public transit, it is also comprised of segmented, incoherent housing. She took inspiration from the architectural language of Havana, Cuba, to design a housing project incorporating repeated, arched facades and centered around a communal courtyard.